On Literacy I On Language

On Perception I On Practices

On Knowledge I Alphabetically

(or suggest a new term to be added)

ON LANGUAGE

To imagine a language means to imagine a life-form. (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations #19)

PLEASE NOTE: Visitors will notice that the topic-specific glossaries are not organised alphabetically. In the paragraphs which follow I aim to explain the logic of the On Language Glossary. It would be safe to say that Wittgenstein sees language as a phenomenon of central concern in his philosophy.

In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he is particularly concerned with describing a logically perfect language. In this early philosophy, he describes language as being made up of propositions (sentences) which describe states of affairs in the world. These declarative sentences make up what is known as Wittgenstein's picture theory of language. And it is a beautiful theory of language. It is one that is fascinated with the capacity of language to depict and simulate actual and possible states of affairs in the world through our words. In this sense, our descriptive sentences become models of reality upon which we can reflect and learn. Even though the Tractatus presents a beautiful picture of language and one I am often drawn to, it is an inadequate picture (in its own admission). The theory fails to take into account a whole range of propositions that are not descriptive, such ethical propositions, religious proposition and even the propositions that make up the Tractatus. For these conceptual sentences to make sense, one must appeal to the communities of practice which use them.

Therefore, in the Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein shifts his attention from the sentence (or the proposition) as the central point of analysis to discourse as the area of fundamental concern. In this rendition of language, Wittgenstein is concerned with the ways in which language is learned and used between people in contexts for - often - non-verbal purposes, which would become known as language games. From this perspective, to understand a language must first involve an understanding of (or at least participation in) actions and objectives of a community of practice. Therefore, mastery of a language is not a matter of simply mastering the formal elements of a language. Mastering a language requires that one masters the uses of language in context with others, which also involves interpreting the intentions and perspectives of others.

LANGUAGE - Wittgenstein presents three dominant images of language. In the Tractatus, he presents language as a system that is akin to how a linguist would describe language. There are nouns, verbs, adjectives, conjunction and more. He presents how the grammar of a sentence clearly presents a picture when all its pieces fall into the right place. By the time of the Blue and Brown Books, Wittgenstein conceives language as a calculus. The language user calculates the situation of language use and chooses the right language to achieve a purpose. The individual learns the rules (or the grammar) to make these choices. In the Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein now conceives of language as language games. The game users go back and forth - to and fro - using conventions of language in particular contexts in the frame of discourse practices to achieve purposes. Every game has a history.

ELEMENTS OF LANGUAGE - Language consists of the following elements that - once integrated - reveal the logic and meaning of our utterances:

- phonology (the sound system and how sounds are combined to form words);

- orthography (conventions of the written [spelling] system used to represent speech);

- vocabulary (the vast accumulation of words used to express our world and our concepts);

- morphology (the components within words that express further meaning, such as prefixes, suffixes, and cognates);

- syntax (the forms and rules upon words are arranged to make meaningful sentences);

- discourse (how sentences are uttered in sequences within an utterance and between utterances to express ideas, intentions and/or purposes); and

- pragmatics (the interpretation of extra-linguistic features in one's physical and social environment that influences how one speaks/writes/reads)

LANGUAGE LEARNING - Learning new elements of language can be seen to involve three core stages: intake, uptake and embodiment. Through sustained, scaffolded practices one develops a repertoire of practices, vocabularies, concepts, forms and contexts that are trialed, incorporated and owned.

AFFORDANCES & EFFECTIVITIES - As defined by Gee (2008), "the term 'affordance' (coined by Gibson 1977, 1979) is used to describe the perceived action possibilities posed by objects or features in the environment ... Any environment in which an individual finds him or herself is filled with affordances." (p. 81) In other words, an affordance contains the possibility of a successful practice, but it does not ensure success. "Even when an affordance is recognized, however, a human actor must also have the capacity to transform the affordance into an actual and effective action. Effectivities are the set of capacities for action that the individual has for transforming affordances into action. An effectivity means that a person can take advantage of what is offered by the objects or features in the environment." (p. 81)

JOINT ATTENTION AND INTENTION - Tomasello (2003) holds that the concepts of joint attention and joint intentional activity are pivotal for language learning and language engagement. In this model, participants in a language event are jointly attending to a phenomenon (e.g. a sunset) and are using language to share observations, interpretations and/or intentions under joint attention. There is an assumption in this exchange that the participants share an intention (or a focus) on the value of the phenomenon and the significance of the phenomenon. In the case of children, it is apparent that both the child and the adult may not share the same intent when investigating the phenomenon. It is through both linguistic and extra-linguistic elements (e.g. hand motions, demonstrations, etc) that either the child or the adult seeks to express his or her intent, focus and requirements.

As Halliday (1993) finds, children start to use non-linguistic, non-symbolic gestures to express intent (or wanting something). Over time, the child is brought into language, and the child comes to express those intentions (and subtleties of intention) through language. As Wittgenstein (2001) observed, "One thinks that learning a language consists of giving names to objects. Viz, to human beings, to shapes , to colours, to pains, to moods, to numbers, etc. To repeat -- naming is something like attaching a label to a thing. One can say that this is preparatory to the use of a word. But what is it a preparation for?" (PI 26)

AFFECTIVE FILTER - Learning a new language is affected by the learner's emotions and motivation. Learners will perform better if they have high motivation and are learning in environments where they are/feel supported. Learners are more likely to take risks and will more fully process the language if they are in supportive environments. If you increase stress factors, then language learning and performance will deteriorate. This deterioration is known as the affective filter. The best learning occurs in environments where there is high motivation with high challenge AND high support.

COMING INTO LANGUAGE - When we learn a language, we are brought into or initiated into the language. The language unfolds, so to speak. This is what I mean by "coming into language". I am referring to the process through which one is brought into a language by others through common lived experience.

SCAFFOLDING - We come to learn methods of activity and systems of knowledge. These methods and systems become reinforced as they are shaped through our interactions with the notion of learning presented to us in a circle of influence. Deep grooves are set in our thinking and our behaviour. In this sense, education proceeded first as a form of training in ways of doing and seeing, which become prototypes for our thinking and decision in future events. Our methods, our experiences, our expectations, our schemas are initially scaffolded for us in the learning process. In turn, these habits, beliefs, rituals and methods become the scaffolding for our engagement with the world in the future. When one is brought into knowledge, one should be brought into content and method at the same time.

BOOTSTRAPPING - Bootstrapping occurs when an individual becomes aware of the patterns and rules governing a phenomenon, such as in language or in a practice. The learner develops an appreciation of and a template for meaningful/permittable combinations or actions. By becoming aware of allowable patterns, one can direct one's attention more efficiently since one is better able to anticipate what to expect or how to act. For instance, the first encounter of a new social situation may give one trepidation. However, regular practice allows one to accumulate the experience to be more confident in what to expect and how to act (to play the game). On the other hand, the experience may also limit creativity since one may develop a familiarity that limits (bootstraps) one's ability to imagine other possible ways of seeing or acting. In relation to language, experience teaches one the patterns of spelling, grammar, and discourse. Therefore, one becomes more efficient at predicting or discriminating correct form and use.

POINTING (OSTENSIVE TEACHING) - In the Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein makes a case that the most rudimentary step of language learning involves the act of labelling. We point to items (or actions) and say "this is a chair" or "this is a block" or "this is an apple" or "this is (the act of) jumping". Language learning must move swiftly beyond this pointing (or ostensive teaching). Learners must speak about apple, do things with block, etc. As a result, one must acknowledge that language is a referential system in its most rudimentary conceptualisation.

PROPOSITIONS - One could state that a proposition is a declarative sentence, but this would not capture the tone or the purpose of a proposition. A proposition is a clear proposal of a state of affairs, which places the reader/listener in a position to assess the significance and/or validity of the pronouncement. For instance, “Nurture - not nature - plays the greatest role in an individual’s development” is proposition that awaits assessment, consideration and verification. "Mr Green is on the street corner," is also a proposition expressing a state of affairs.

STATES OF AFFAIRS - Wittgenstein insists that propositions describe states of affairs. Or, propositions arrange words in syntax, which refer to the world, and which come to represent how things are or could be, or which could be asserted. In this case, a state of affairs is a proposition or a series of proposition which come to indicate how "things stand" in a given case. "What is the state of affairs?"

REPRESENTING - We do not merely record experiences and events when we speak or write or paint. We make choices that serve to represent events in a particular way. The representation is an interpretation or rendering of events, which can provide an insight into the way that one perceives or reacts to phenomena. A particular representation can serve to corrupt events or experience yet a representation can also give peace. There is often a way to represent events in multiple ways which can lead to quite different reactions.

DESCRIPTIONS - To describe is to lay out the details of a case clearly and thoroughly and without comment, embellishment or judgement. To explain is to provide comments on observations, to provide reasons for why something occurred, and to lay judgements on events. For Wittgenstein, “I believe the attempt to explain is certainly wrong, because one must only correctly piece together what one knows, without adding anything.” (Wittgenstein, from Remarks on Fraser’s Golden Bough)

PROJECTIONS - Wittgenstein stated that proposition were in need of projection. In this sense, projection refers to the ability to derive meaning from a statement. Wittgenstein uses the visual metaphor of a film projector, which reads the film and magnifies that film into a rich, vivid picture. Thereby, a statement is only meaningful once it has been projected/interpreted. Consequently, one cannot guarantee that one will be understood, since being understood relies on the sharing of a common language, a grammar and certain conventions of meaning-making.

PICTURE THEORY - What is known as "the picture theory" lies at the core of the Tractatus. In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein held that a proposition that made sense would generate a picture of a state of affairs. Thereby, in language, people could navigate different events or facts by exchanging propositions (or pictures). As a consequence, one assesses the truth of a proposition by appealing to whether the event pictured did or did not occur.

In terms of logic, Wittgenstein challenged the notion that one could determine truth in any way from following the logic of propositions alone. Instead, one could only assess the states of affairs that a proposition referred to. Most significantly, Wittgenstein presents this wonderful image of the function of language; it allows people to exchange thoughts and images with one another, therefore enabling humankind to communicate, share and build together.

GRAMMAR - When Wittgenstein refers to grammar it is not always in the traditional notion of the term. In some cases, grammar refers to the rules that govern language which determine whether an expression makes sense. In the words of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Wittgenstein adopts the term ‘grammar’ in his quest to describe the workings of this public, socially governed language, using it in a somewhat idiosyncratic manner. Grammar, usually taken to consist of the rules of correct syntactic and semantic usage, becomes, in Wittgenstein's hands, the wider—and more elusive—network of rules which determine what linguistic move is allowed as making sense, and what isn't.” -- http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/wittgenstein/#Pri

CALCULUS - Before Wittgenstein conceived of language as "language games", he conceived of it as a calculus. In other words, he presented a picture in which the language user assesses the situation before him or her, then calculates the scenario, and selects the right language to achieve a given goal. To decipher the meaning, one would need to assess both the statement itself and other possible statements that could have been made. By doing so, one would be able to understand the intention of statements based on choices made and the alternatives that were avoided. Conceptualising language as a calculus would pave the way for Wittgenstein's use of language games as a unifying features of his later philosophy.

ELABORATED AND RESTRICTED CODES - In his work on linguistics and sociology, Basil Bernstein suggests a rough model to distinguish between what he refers to as an "elaborated code" and a "restricted code". In this case, “code” refers to the language that is used by an individual or a group. In the case of an elaborated code, the speaker will select from a relatively extensive range of alternatives. Propositions express a specific meaning based on the choices made by the speaker and those choices which are omitted or avoided. We imagine a language that is rich with interchangeable parts, specific terminology and a consciousness of the consequences of word choice.

In the case of a restricted code the number of choices is often severely limited, and the speakers tends to navigate through a narrow, often cliched language base. Language is often less technical and it relies upon common phrases used regularly by the social group. The speaker may lack the language choices that would enable him or her to express exactly what is being felt, thought and/or experienced. Consequently, the individual may resort to language and attitudes that are typical within the group. In some cases, it can argued that the user is not critically aware of subtle significance of their language choices, and they can also be evasive if called upon to elaborate or explain themselves further.

On a psychological level the codes may be distinguished by the extent to which each facilitates (elaborated code) or inhibits (restricted code) one’s ability to explicitly verbalise individual thoughts, feelings and responses. It is often the case that a restricted code has the capacity to become elaborated; however, it is often seen as inferior in formal educational contexts and is therefore not opened up to critical examination and extension.

SRAFFA’S GESTURE - Wittgenstein’s early philosophy became undone in a quick remark from the Italian economist Piero Sraffa. Wittgenstein previously claimed that all meaning could be deciphered by appealing to the grammatical structure of an expression. However, Sraffa made a hand motion under his chin, which is a sign of contempt in Italy, and asked, "what is the grammatical form of this?" Wittgenstein was flummoxed. He couldn't appeal at all to structure for its meaning. He had to appeal to its use (or its practice) within a form of life. This was the moment when Wittgenstein proclaimed that meaning is use and "words are deeds" and that one must attend to context as well as form to understand the logic and nature of language.

INTENTION - To intend something requires both a purpose and a concept of the expected or possible outcome of the action. In social practices, intention usually involves both parties being aware of the rules of discourse and the consequences of certain discourse. How is it that she knows to pick up the phone and hand me it to me when I call out "Phone, please!"? How is it that one knows the intention of a prayer upon hearing it and bowing one's head in a congregation? How is it that one knows that a person intends no offence when he stands much too closely? Reading and acting upon intention requires a certain level of familiarity with how to read the signs of a certain practice. It is also easy to misread an intention or to miss an intention altogether.

DISCOURSE - Discourse refers to the exchange of ideas through an interchange between speakers. A discourse analysis involves an analysis of the types of exchanges, their conventions, the roles taken by the speakers involved, and the dominant themes which direct and control the conversations. Discourse can refer to a single instance (such as a conversation) and it can refer to collective conversations that are taking place over time. One can tell quite a bit about people by observing (a) what they tend to speak about, (b) how they speak, and (c) the roles taken by participants through the activities of speaking. In the field of Systemic Functional Linguistics, any message is considered to have (i) content, (ii) a form, and (iii) participants, also known as field, mode and tenor.

In relation to discourse, James Paul Gee emphasised that any message contains two dimensions. The little "d" discourse is the language itself, whether it is oral or print or digital. However, for any text to be understood, one needs to know the context, the culture and conversation of which the text is part. Therefore, one must also be able to read the big "D" discourse, or know and interpret conventions of context and culture so as to engage in the discursive and associated non-discursive activity.

COMPONENTS OF A MESSAGE - Any message is found to have a field (a content), a mode (a form) and a tenor (an audience). Even the cry "Help!" would satisfy all three elements. It has a term with a content in the form of an imperative exclamation for an audience who is to either to read the exclamation seriously (if a bear is on attack) or with irony (if instead a little baby is the attacker).

Gee (2003) provides the following example:

- Hornworms sure vary a lot in how well they grow.

- Hornworm growth displays a significant amount of variation.

Both convey the same field (content) but their modes are impacted by the intended audience and - consequently - the tenor of the utterance.

LANGUAGE GAMES - As a general rule, a language game is an instance of language exchange. To understand and analyse the exchange, one must look at the language used as well as the roles that the participants are taking in the activity, which is taking place in a form of life. We are curious as to how different moves (uses of language) are used and responded to in the midst of the activity. For instance, Wittgenstein presents a scenario between a builder and an apprentice in which the builder calls out for different materials and the apprentice learns to identify the materials and also knows that he must bring the materials to the builder when they are called out in a particular way in the particular situation. So, to be more exact, the exchange is part of a practice, which means one learns the conventions, context, purpose, terms and form of the language game.

Consider the telling of a joke or the reciting of a prayer or the performance of a play. Also, look at how certain language games (or practices) become unacceptable (such as sexist and racist banter) or obsolete (such as the mannerism of 18th century English polite discourse). In addition, language games are played out to negotiate and navigate the meaning and relevance of concepts, such as the right to free speech, or the role of religion in a secular society. These debates are ongoing practices, which have evolved to reflect different "teams", each attempting to achieve intended or unintended outcomes.

LANGUAGE/LITERACY AS SOCIAL PRACTICE - This concept is an extension of Wittgenstein's Language Games premise. That is, language and literacy are tools used within culture to achieve certain ends. As social practices, language and literacy consist of a repertoire of genres in context. They include events, practices, spaces and material artefacts. In other words, every instance of language use is an event that is part of a particular practice that often is practiced in a set of social spaces in which certain material resources are used in purposeful activity. For instance, the event of reading a nighttime book with a child is a distinct practice that exhibits each of the above features and is based on a culture of book reading that is valued by the participants. Similarly, military orders delivered to a platoon in training would also require the learning of conventions in joint, purposeful activity that used non-discursive materials for non-discursive ends. We learn language and literacy not as ends in themselves but as vehicles in our forms of living.

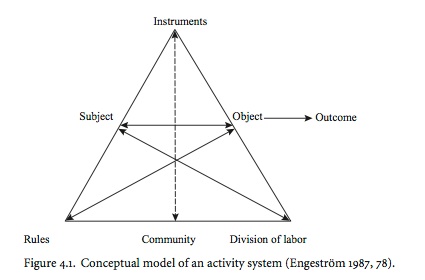

ACTIVITY SYSTEMS - An activity system describes the interaction between people and resources with certain intended outcomes. An activity system involves the integration of

- instruments (various tools and technologies),

- rules (norms of use), and

- division of labor (the differential expertise of different actors in the system).

Various other relationships in the model capture the diverse ways in which

- subjects (actors),

- the object (goal) of the activity system, and

- the community (various types of actors in the system)

interrelate with each other and with the instruments, rules, and division of labor to achieve particular outcomes.

SITUATED LEARNING - When we learn, we learn interactively with others to use such learning to approach and/or solve problems. Therefore, learning is not some abstract activity or content. Instead, there is a context in which learners are situated, and the context/culture provides a justification/rationale for learning. Learning is situated. The learner embodies the learning in its application.

SEMIOTIC DOMAINS - A semiotic domain is an area of knowledge, such as basketball, gardening, cooking, physics, hunting, bush tucker, etc. A semiotic domain includes knowledge, concepts, language, contexts, etc. Throughout one's life, one is brought into a range of semiotic domains in learning interactively with others.

CONCEPTS - Concepts can be represented by words like peace, freedom, sustainability, equity and more. They gravitate our attention to certain values or expectations. Concepts become central to public and communal discussions. It is interesting to explore how certain concepts become central to our discourse whereas other concepts fade into the margins. For Vygotsky, "[concepts] are those means that direct our mental operations, control their course, and channel them toward the solution to the problem confronting us' For Wittgenstein, "Concepts lead us to make investigations; are the expression of our interest, and direct our interest."

BEETLE IN A BOX - (it is arguably Wittgenstein's most famous thought experiment about language.) Wittgenstein asks the reader to imagine people sitting around a table who each has a beetle in his/her box. which each individual is holding. Then, the people are all told that each box holds a beetle. Subsequently, the group is asked, "do you know what is in each other's box?" The group responds without hesitation, "of course, you just told us there is a beetle in each box." The unanswered reply would go something like this, "how can you know? You haven't looked into the boxes." So, what's the point?

Well, one doesn't necessarily need to 'look inside someone head" to know what he or she is thinking when he or she speaks. To understand a thought, it is important to share a common language and - perhaps - certain concepts and values in common. It is important to share certain experiences and associations with our words. Language enables people to converse about beetles, about pain, about God, about Hamlet and such without necessarily having the exact same mental images or constructs. People swap ideas and manipulate what thoughts lie in the box of the head through their discourse. In this picture, meaning is generated and is circulated between people (with an impact on the individual) rather than percolating from within.

FAMILY RESEMBLANCES - This is one of Wittgenstein's most significant observations about language. It states that a concept - such as beauty or truth - represents a family of criss-crossing traits but no essential qualities that all beautiful or truthful things must hold in common. This applies to the vast range of words, such as “plants” or “games” or “social justice” or “mathematics”. For instance, a sunset is beautiful as well as a gothic cathedral. What does a sunset or a cathedral hold in common? Also, can we live in a world in which some truths are factual truths and others are aspirational. It is true (factually) that the sun rose yesterday and it is true (aspirationally) that everyone deserves their human right to be respected.

What is the point, then? Well, in the past philosophers battled to reach THE essential definition of truth or of beauty or of morality or of education. For Wittgenstein, this pursuit inevitably leads to dilemmas, since there will be cases that do not fit the definition that are unfairly marginalised in the interests of creating a neat definition. Instead of seeking an essential definition of our words and concepts, philosophers should describe all the varied manifestations of the concept in actual use. The philosopher can lay these cases openly and plainly to see. Only then can one attempt to understand the nature of the concept even if we are not able to formulate that definition in words.