Establishing Practices

"At the very least, a practice is something people do, not just once, but on a regular basis. But it is more than just a disposition to behave in a certain way; the identity of a practice depends on not only on what people do, but also on the significance of those actions and the surroundings in which they occur." (Stern, 2004, p. 166)

In the previous pages, we have discussed the balance of instruction and the stages of literacy development. It is at this point that we would like to "get to the rough ground" and emphasise the importance of establishing routines and practices based on quality teaching principles that progressively build and extend a learner's capabilities. We are contrasting what may appear as sporadic, isolated activities with activities that are carefully arranged and which contribute to the development of meaningful literacy skills.

We will spend the present discussion on the following: that developing language, literacy and learning skills involves a range of practices through which learners develop skills in decoding, comprehension, composition and critical thinking. With that central term (practices) laid out onto the page, our attention now turns to defining what - indeed - is a practice, or "what makes a practice?"

Sometimes the best way to approach this is to imagine the culminating event that is the fulfilment of a range of building blocks acquired over time that finds closure in the ability to "do something". This may be cake baking, fly fishing, trumpets blowing, or advanced spelling. For instance, the ability to write a great short story, prepare for that spelling bee, or draft a persuasive essay involves the culmination of heaps of practice, revision, learning and exploring. It is also often impacted by the practices and expertise of others, who instil the appreciation and the tips of - let’s say - storytelling into the learner. It is often necessary for the individual to have certain experiences to develop the skills that are synthesised into a practice and rewarded as a practice. The learner is also benefited if he or she lives in an environment that regularly reinforces the practice of - again - storytelling, and which contain many ways to unmask the mysteries of the craft.

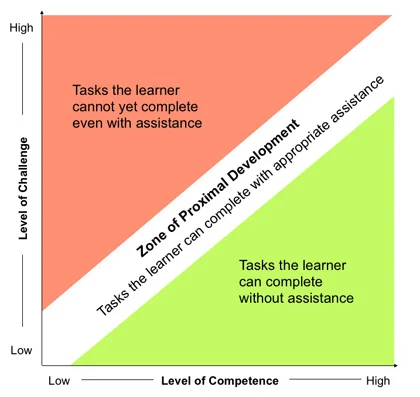

When we speak of developing practices, we similarly speak of “scaffolding” practices. Scaffolding refers to supports that teachers and/or parents provide to learners during some act of learning or problem-solving. These supports take the form of activities, axioms, mnemonics, reminders, hints, routines and encouragement, which are essential to ensure successful completion of the task. An important feature of scaffolding - especially in authentic, apprenticeship contexts - is keeping the task/goal whole and visible (Shepard, 2005). For instance,

- when a child is learning to sew or set the table, adults may step in and help with the trickiest most difficult part — threading the needle or taking the breakable glasses down from the top shelf;

- in classrooms, teachers may help students with the research before sending them to the library. When a student is stuck because he or she can’t find information on a given topic, the teacher may suggest a new search term or help the student narrow the topic (Shepard, 2005);

- when a student is learning to write a short story, the teacher might divide the story into its most significant parts (orientation, complication, rising action, conflict, climax and resolution) to gradually build the learner's skills; or

- when learning to write an argumentative paragraph, one might suggest the clever "burger" device to make visible the implicit structure of the form.

Gradually, as competence increases, the teacher and/or parent cedes more control to the learner. To be successful, the learner must also come to understand and take ownership of the goal. In other words, what becomes necessary is the individual's "willingness to engage with such activities in a particular way, thus changing ‘mere’ activities into practices where standards of excellence do matter.” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010 pg 196) The two elements of this quote are quite significant. We would like to draw our attention to two factors (a) the ”willingness to engage" and (b) "where standards of excellence do matter." In the first instance, it is important to mention the implied term: motivation. The question being, is the learner motivated, aware and strategic enough to engage in the activities to such an extent so as to develop the practice? We will ignore the complexities of motivation for the present moment. In the second factor, engagement in activities will be impacted by the extent to which the individual understands and appreciates what "the standard of excellence" - or a successful practice - would look like. Does the learner have access to models that exemplify goal states on the way to excellence and encouragement to meet these goals?

The above suggests that a learner ideally must comes into a practice as a member of a community or culture, so to speak. This reminds me of the Australian novel Maestro by Peter Goldsworthy. In the novel, the adolescent protagonist is a talented pianist growing up in Adelaide and - subsequently - Darwin. His parents provide the optimal conditions and support that allow the young man to develop into a technically sound and accomplished young musician in Australia. It is only when he encounters a new teacher - a pianist from old Europe - that the young man comes to realise that there is something missing in his repertoire that will limit the possibility for his talent to be fully realised. He is missing culture. The Australian culture lacks the depth of connection to the music, and so the young protagonist becomes an adept pianist but not a profound one. At first, he rebels against this realisation, since all signs in Australia point to his technical and musical prowess. However, it is clear as the novel unfolds that the young man lacks access to the culture and the temperament behind the music to really understand the depth of its practice and the role that the music plays for those who are immersed in its history. He has the capacity to alter his musical practice, but that might require an initial act of submission and immersion.

If we return to a previous example, we would see that being able to write an absolutely great story is not enough evidence to suggest that the individual has acquired the practice. It shows that the individual has completed the activities to write that one great short story but not necessarily adopted the practice of story writing. The writing of a second “fantastic short story" would be strong evidence to suggest that the practice has evolved. The fact that the individual writes a second story without any prompting or with only limited prompting would also be great evidence. If the person could articulate how he or she went about writing both the original short story and a subsequent story, then we would be quite satisfied. If the person could also articulate the purpose and/or motivation of the story writing, then the person would be approaching the ability to express his or her appreciation of the practice's significance. If the person could join a peer group who discussed the merits of short fiction, then we could say that the learner was well on his or her way to membership in a community of practice.

Being initiated into such a practice - therefore - involves the internalising of - what we might call - deliberative talk. For instance, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein models this aspect by presenting the inner monologue of a character who is building something:

Every now and then there is the problem “Should I use this bit?” — The bit is rejected, another is tried. Bits are tentatively put together, then dismantled; he looks for one that fits etc, etc.. So I sometimes make him say “No, that bit is too long, perhaps another’s fit better.” — Or “What am I to do now?” — “Got it!” — Or “That’s not bad” etc. ...

"If he has made some combination in play or by accident and he now uses it as a method of doing this and that, we shall say he thinks. — In considering he would mentally review ways and means. But to do this he must already have some in stock. Thinking gives him the possibility of perfecting his methods. Or rather: He ‘thinks’ when, in a definite kind of way, he perfects a method he has." (Wittgenstein, Zettel #100 & 104). Whilst the character's dialogue is personal and internal, this internal voice - or self talk - is developed in practice with others:

“Our deliberations seem to be entirely personal and self-determined - yet which obviously derive from previous conversations with others, in which their voices and perspectives are represented in one’s own internal deliberations. Often this dynamic is what we call ‘conscience.’” — (Burbles and Smears, 2010, pg 180)

In refining a practice, we become conscious of our actions, their intentions and the consequences. Therefore, a practice “is something people do, not just once, but on a regular basis.” (Stern, 2004, pg 166). For some reason, people pray, brush their teeth, complete their tax, hike in National Parks, long for the next dance, etc. Each “activity” is part of - let’s says - religious practices, hygienic practices, economic practices, artistic practices, social practices and more. Each practice is much more than the sum of its parts. The activities become part of a way of acting, anticipating and performing. For instance, the combination of spelling practice, shared reading, guided comprehension, writing practice, concept exploration, and experiential learning amounts to more than a collection of disparate activities. They amount to a form of life, and they rely upon resources, other participants, teachers, a sense of attachment, cultural artefacts, instruction (or initiation) and more. Time and space must be carved out in the great hurly burly of life so that the practice can grow, flourish and evolve. Richard Allington (2002) captures this well when he describes the six T's of effective literacy instruction:

- Substantial time allocated to real practice in reading and writing;

- Availability of texts that are engaging and suitable for learners;

- Teaching that is of the utmost quality, which is adaptive and which scaffolds the development of key skills and understandings;

- Teachers who facilitate rich "talk" (conversations) that allow learners to solidify and expand on ideas;

- Tasks that are deep, authentic, and purposeful; and

- Assessments (or "testing") that provide real information about a learner’s progress toward complete, comprehensive literacy (Allington, 2002)

Therefore, “one can distinguish activities, games, practices and rituals ... When we consider a ‘practice’ we must think about (1) how they are learned - for instance through imitation, initiation, instruction and so forth; and (2) how they are enacted.” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010, pg 193 - 194) It is a practice to commit facts to memory and to draw connections between this knowledge that will enhance one's understanding. This act of developing knowledge and understanding involves many stages and processes, which a person (in school) is often asked to do without clear guidance. For some, the practice is obscure and there are few opportunities for one to find guidance. For others, the practice is moulded and shaped and reinforced by a parent, teacher, family friend, and/or peers. Vygotsky (1978) would remind us 'every function in the child's cultural development appears twice: first on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people..., and then inside people... All higher [mental] functions originate as actual relations between human individuals' (p.57)

So ... how do we make certain activities part and parcel of the practices of home, school, the community, etc? What are the material and social conditions that make this happen? What roles do adults and peers play in establishing the conditions of a practice? Is it realistic that all budding "apprentices" will have access to "teachers" (including parents) with sufficient expertise and wherewithal? Overall, how does something become a practice and, through practice, how does the learner's engagement with the world change?

To begin with, we must acknowledge that any practice occurs in environments through engagement with others (peers, adults, etc). And particular environments provide better venues for certain practices to prosper than others. In this case, we may illustrate how the multiple conceptions of literacy practices - for instance - take shape within the dynamics of a given household or classroom (Heath, 1983). In some homes, it is not surprising for one to imagine how bedtime reading, alphabetic flashcard practice, scaffolded writing instruction and language-in-context practice can occur with only limited orchestration. The adult has a bedtime routine of rich reading of favourite books (building vocabulary), time set aside to play with enticing alphabetic games (enhancing word recognition), time to write a birthday card to grandma (modelling of genre conventions), and an emphasis on language in the act of - for instance - baking a cake (learning vocabulary connected to a valued activity).

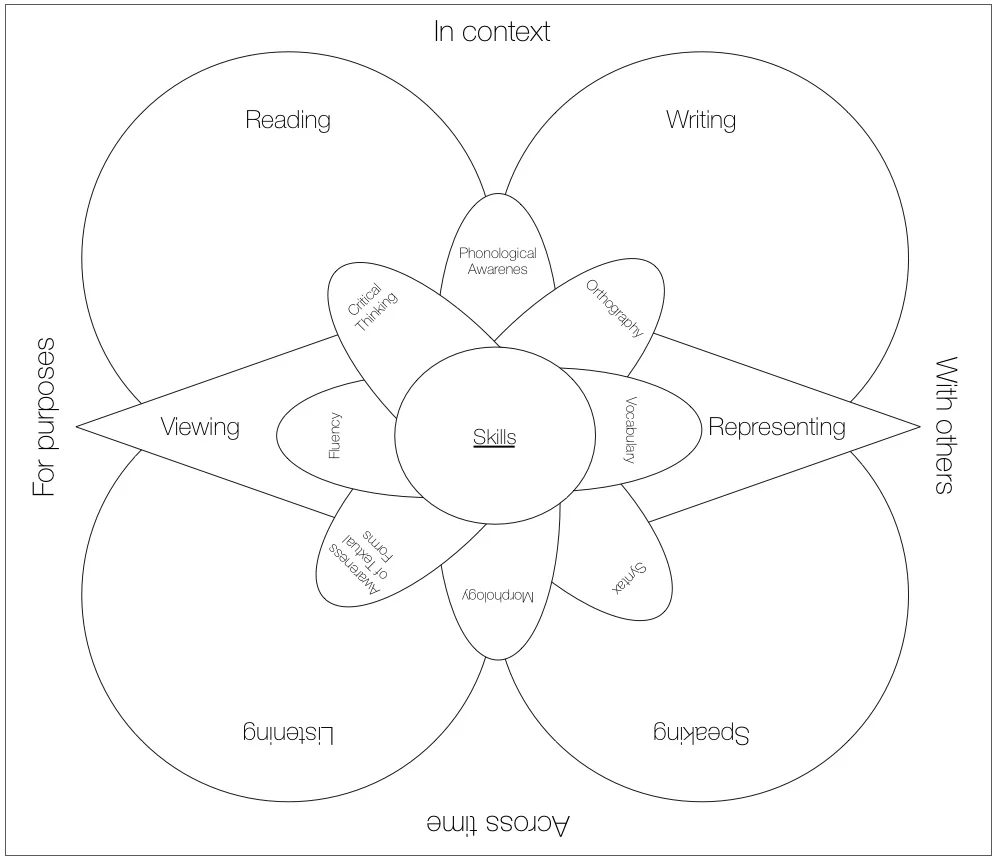

In the above example, each activity emphasises different aspects of language and literacy development, and each activity - occurring more or less frequently - is integrated through the joint intentional activity of the adult & child. If more direct, formal instruction is necessary, it is woven into the fabric of the overall practice. Therefore, “every instance of the use [or participation in a practice] … is the culmination of a process of socialisation.” (Phillips, 1979, pg 126). Through this journey, the learner “develop[s] an impressive variety of skills.” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010, pg 191). As stated in the essay "A Framework for Considering Literacy Instruction" the inculcation of such skills involves the careful arrangement of:

- (a) systematic instruction in core skills,

- (b) meaningful routines and practice in reading and writing, and

- (c) scaffolded practice of literacy in authentic and/or disciplinary contexts.

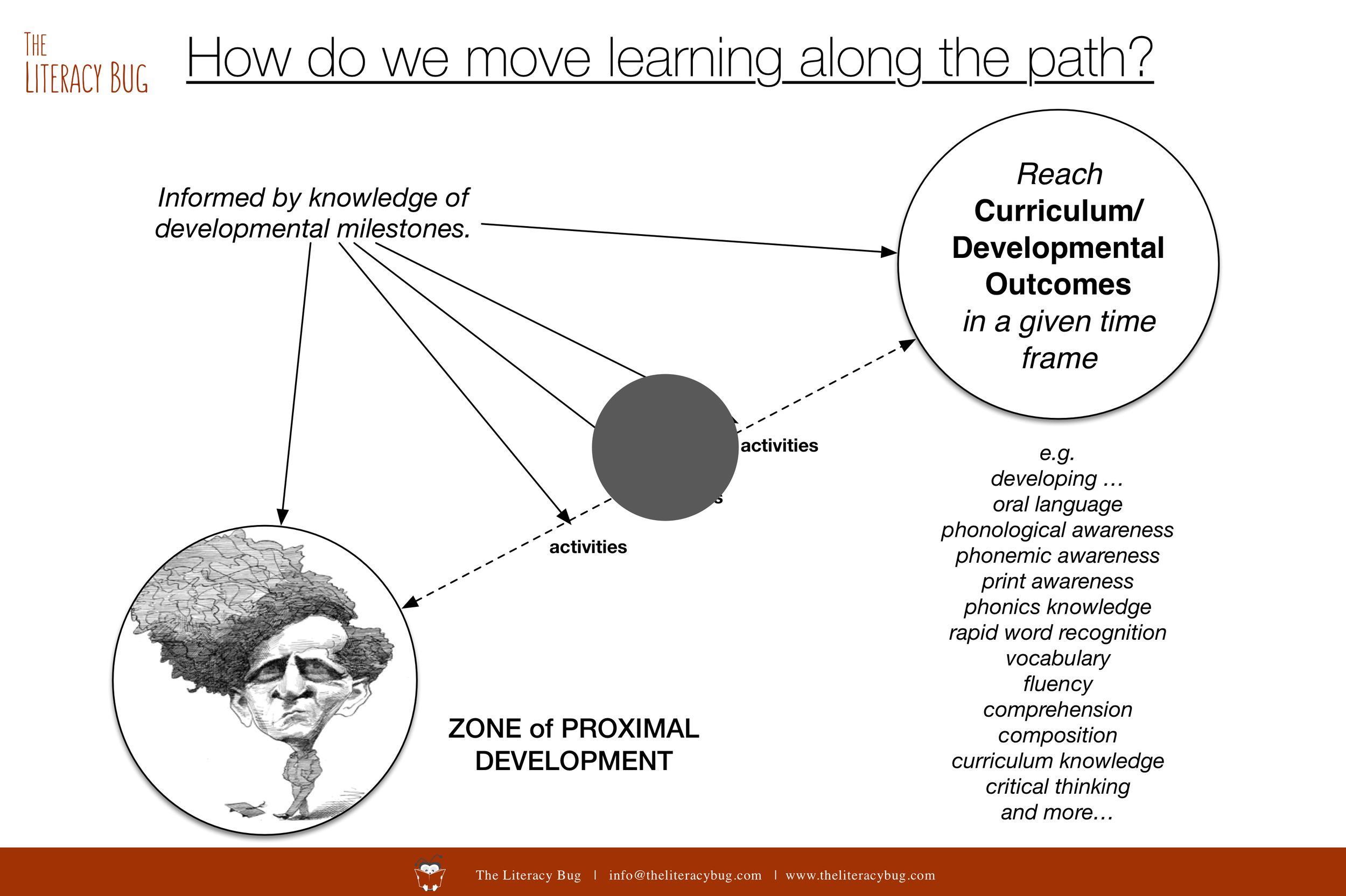

The images to the left/above extend this thinking. We see how literacy practices involve a range of elements, including intentional (instructional) conversations; vocabulary development; word/language study (including phonemic awareness); reading for fluency and comprehension; writing and composing; developing knowledge; and the fostering of interests, habits, routines and expertise. We see the need for a parallel emphasise on core skills, meaningful routines and authentic practices. We acknowledge that time must be plentiful, resources made available, teaching made accessible and partnerships formed (between home, school and community) if literacy practices are to emerge, deepen and mature.

The most skilled teachers, families, communities, etc. are those who orchestrate a variety of experiences for learners in different environments which are able to bring about meaningful routines, habits, ceremonies, perspectives and more. They are sensitive to the needs of the learners and they carve out time and space so that learning, development and communication are happening. When you look down at the daily, weekly, monthly and term calendars of exemplary teachers, you see that careful arrangement of opportunities that provides time for explicit and scaffolded instruction as well as spaces for creativity, exploration, application and inspiration (Chall, Jacobs & Baldwin, 1990; Snow, et al, 1991). When you look at the arrangement of classroom spaces, home environments and community resources, you are likely to see literacy- and learning-rich environments that facilitate the practices that take place within them. In the classroom, you see literacy rotations, regular and diverse readings, incursion from the community, formative assessments, and research into relevant, purposeful tasks. It appears that teachers and students know where they are going and what needs to be done.

"According to research, amount of teaching is the single most important determinant of amount of literacy learning [and practice] (Carroll, 1963; Siedel & Shavelson, 2007; Walberg, 1986). Research has not been very precise about what counts as teaching, but it certainly would include teacher presentations, modelling, and explanations. It would also usually include many student activities such as guided practice or independent practice. Some researchers make the valuable distinction between allotted time and engaged time." (Shanahan, 2008 pg 3-4)

Click on image to expand

The following are some core principles to be mindful of when thinking about factors that impact our engagement in practices.

- To become a participant in the practice - whether artistic, athletic, religious, etc - involves an engagement in a whole raft of behaviours, rules, perspectives, and more.

- Practices are "part and parcel of our early socialization in life, [through which] we each learn ways of being in the world, of acting and interacting, thinking and valuing, and using language, objects, and tools that crucially shape our early sense of self.” (Gee, 2008, pg 100)

- Practices rely upon resources, other participants, a sense of attachment, cultural artefacts and avenues to be rewarded for the practice.

- It is much easier for a practice to be adopted when it builds upon (or extends) “the informal practices [people already] find themselves involved in.” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010, pg 196 - 197).

- And furthermore, a practice is only possible "if one trusts something,” which includes trusting others as well as the situations in which we find ourselves in. (Klagge, 2011, pg 66)

- Consequently, “it is [much] easier to be a ‘tacit teacher’ within an ongoing community of practice, where one is not the only influence drawing learners into reflective participation; conversely, it is harder to be a ‘tacit teacher’ when a cacophony of other influences distract and compete with one’s own influence.” (Burbles, 2010, pg 212)

- Practices can be defined by “how they are learned - for instance through imitation, initiation, instruction and so forth..” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010, pg 193 - 194). The novice proceeds to quite literally practice “a certain kind of know-how [that] is gained through repetition: watching and doing the same thing over and over again, under the watchful eye of a skilled practitioner." (Burbles, 2010, pg 208) This is also described as a process whereby, “newcomers pick up both overt and tacit knowledge through a process of guided and scaffolded participation in the community of practice, a process that has been compared to apprenticeship.” (Gee, 2008, pg 91 - 92).

- This is teaching by any other name, otherwise described as “the structuring provided by a community or practice, [which is] physically necessary because the very possibility of any learning at all is the presence of exemplars and models.” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010, pg 186).

- We want to focus on, "people’s willingness to engage with such activities in a particular way, thus changing ‘mere’ activities into practices where standards of excellence do matter.” (Smeyers and Burbles, 2010 pg 196).

- "The child's understanding is not achieved in an instance or a flash, but requires multifarious repetition in multifarious contexts." (Moyal-Sharrock, 2010, pg 6).

- “What seems to be needed is the development of a theory of social learning which would indicate what in the environment is available for learning, the conditions of learning, the constraints on subsequent learning, and the major reinforcing process.” (Bernstein, 1964, pg. 55)

We - then - return to questions raised above ... how do we make certain activities part and parcel of the practices of home, school, the community, etc? What are the material and social conditions to make this happen? How does something become a practice and, through practice, how do we see improvement?

Click on image to expand.

We must emphasise the importance of motivation, understanding, effective teaching, and access to the space and time for engaged concentration. As the diagram to the left illustrates, we must also consider factors internal to the individual (e.g. cognitive and language processing), factors in the environment (ecological factors), and factors impacting motivation and engagement (psychological factors) (Chiu, McBride-Change & Lin, 2012). In the view of Timothy Shanahan (2008), the five most important aspect of literacy learning are (1) amount of teaching/time, (2) access to appropriate content, (3) quality of instruction, (4) motivation of the learner, and (5) whether the instruction/resources align with the needs of the learner. And from a sociological perspective it is important to remember how a child’s acquisition of knowledge (and literacy) is influenced by five characteristics of the sociocultural context: (a) the identity of the participants, (b) how the activity is defined or executed, (c) the timing of the activity, (d) where it occurs, and (e) why children should participate in the activity. (Tharp and Gallimore, 1988)

As mentioned elsewhere, it goes without saying that the experienced language/literacy user takes many items for granted. It is helpful to forget that it was once quite a challenge to read and hear that code; to shape letters with delicacy; to retrieve a word from memory and understand its spelling; to form a sentence; to make sense of sentences whether they appear in poetry or in a textbook; to write in a manner fitting the occasion and the audience; and to allow oneself the time to read-interpret-and-learn.

This section asks readers to reflect on the principles that influence the ways in which we manage environments, activities, resources, people and expectations. In the future, I hope to provide some concrete examples in different contexts which would help us better reflect upon the impact of our activities on the daily, weekly, monthly, quaterly, and yearly levels. We should seek out examples that magnify the importance of forming partnerships amongst parents, teachers and communities so that language, literacy and learning practices can permeate these spheres, as we explore the conditions that give rise to learning practices and we consider how to be more inclusive in our teaching. The discussion borrows sparingly from an extended essay (Why We Do What We Do?) which we encourage you to visit when/if you have the time. We also encourage you to visit the Practices Glossary, which also presents a number of key concepts on the topic. Please explore and enjoy!

“I do not remember that first moment of knowing I could read, but some of my memories - of a tiny, two-room school with eight grades and two teachers - evokes many pieces of what the language expect Anthony Bashir calls the ‘natural history’ of the reading life. The natural history of reading begins with simple exercises, practices, and accuracy, and ends, if one is lucky, with the tools and the capacity to ‘leap into transcendence.’

“My other vivid memory of those days centres on Sister Salesia, trying her utmost to teach the children who couldn’t seem to learn to read. I watched her listening patiently to these children’s torturous attempts during the school day, and then all over again after school, one child at a time ... My best friend, Jim, ... looked like a pale version of himself, haltingly coming up with the letter sounds Sister Salesia asked for. It turned my world topsy-turvy to see this indomitable boy so unsure of himself. For at least a year they worked quietly and determinedly after school ended.” (Wolf, 2008, p 109 - 112)

References

Allington, R. L. (2002). What I’ve Learned about Effective Reading Instruction from a Decade of Studying Exemplary Elementary Classroom Teachers. The Phi Delta Kappan, 83(10), 740–747.

Bernstein, B. (1964). Elaborated and Restricted Codes: Their Social Origins and Some Consequences. American Anthropologist, 66(6_PART2), 55–69. doi:10.1525/aa.1964.66.suppl_3.02a00030

Burbles, N. (2010). Tacit Teaching. In M. Peters, N. Burbles, & P. Smeyers (Eds.), Showing and doing: Wittgenstein as a pedagogical philosopher (pp. 199 – 214). London: Paradigm Publishers.

Burbles, N., & Smears, P. (2010). The practice of ethics and moral education. In M. Peters, N. Burbles, & P. Smears (Eds.), Showing and doing: Wittgenstein as a pedagogical philosopher (pp. 169 – 182). London: Paradigm Publishers.

Carroll, J.B. (1963). A model of school learning. Teachers College Record, 64, 723–733.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The Reading Crisis: Why Poor Children Fall Behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chiu, M. M., McBride-Chang, C., & Lin, D. (2012). Ecological, psychological, and cognitive components of reading difficulties: testing the component model of reading in fourth graders across 38 countries. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 391–405. dos:10.1177/0022219411431241

Gee, J. P. (2008). A sociocultural perspective on opportunity to learn. In P. Moss, D. Pullin, J. P. Gee, E. Haertel, & L. Young (Eds.), Assessment, equity, and opportunity to learn (pp. 76 – 108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klagge, J. (2011). Wittgenstein in exile. Cambridge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Moyal-Sharrock, D. (2010). Coming to Language: Wittgenstein’s Social “Theory” of Language Acquisition. In SOL Conference 6-8 May 2010. Bucharest.

Seidel, T. & Shavelson, R. J.(2007). Teaching effectiveness research in the past decade: The role of theory and research design in disentangling meta-analysis results. Review of Educational Research, 77, 454-499.

Shanahan, T. (2008). Literacy across the lifespan: what works? Community Literacy Journal, 3(1), 3–20.

Shepard, L. A. (2005). Linking Formative Assessment to Scaffolding. Educational leadership, 63(3), 66-70.

Smeyers, P., & Burbles, N. (2010). Education as initiation into practices. In M. Peters, N. Burbles, & P. Smeyers (Eds.), Showing and doing: Wittgenstein as a pedagogical philosopher (pp. 183 – 198). London: Paradigm Publishers.

Snow, C. E., Barnes, W. S., Chandler, J., Goodman, I. F., & Hemphill, L. (1991). Unfulfilled expectations: home and school influences on literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stern, D. (2004). Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tharp, R. G., & Gallimore, R. (1988). Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walberg, H. J. (1986). Syntheses of research on teaching. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research and teaching (pp. 214–229). New York: Macmillan.

Wittgenstein, L. (1967). Vettel. (G. E. M. Anscombe & G. H. von Wright, Eds.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Wolf, M. (2008). Proust and the squid: the story and science of the reading brain. Cambridge: Icon Books.