It is with great pleasure that we share another Activity Presentation. This time we explore Word Sorts.

Word Sorts is a simple way to encourage learners to develop an understanding of the predictable patterns when reading and spelling English words. In short, each word sort activity requires learners to examine a set of words, and to sort (or categorise) these words into common patterns whilst identifying exceptions to the rule. This brief activity is designed to be done daily (or regularly) as learners "study" different sets of pronunciation and spelling patterns. In doing so, learners explore how to blend and segment various consonant and vowel sounds in simple to more complex words.

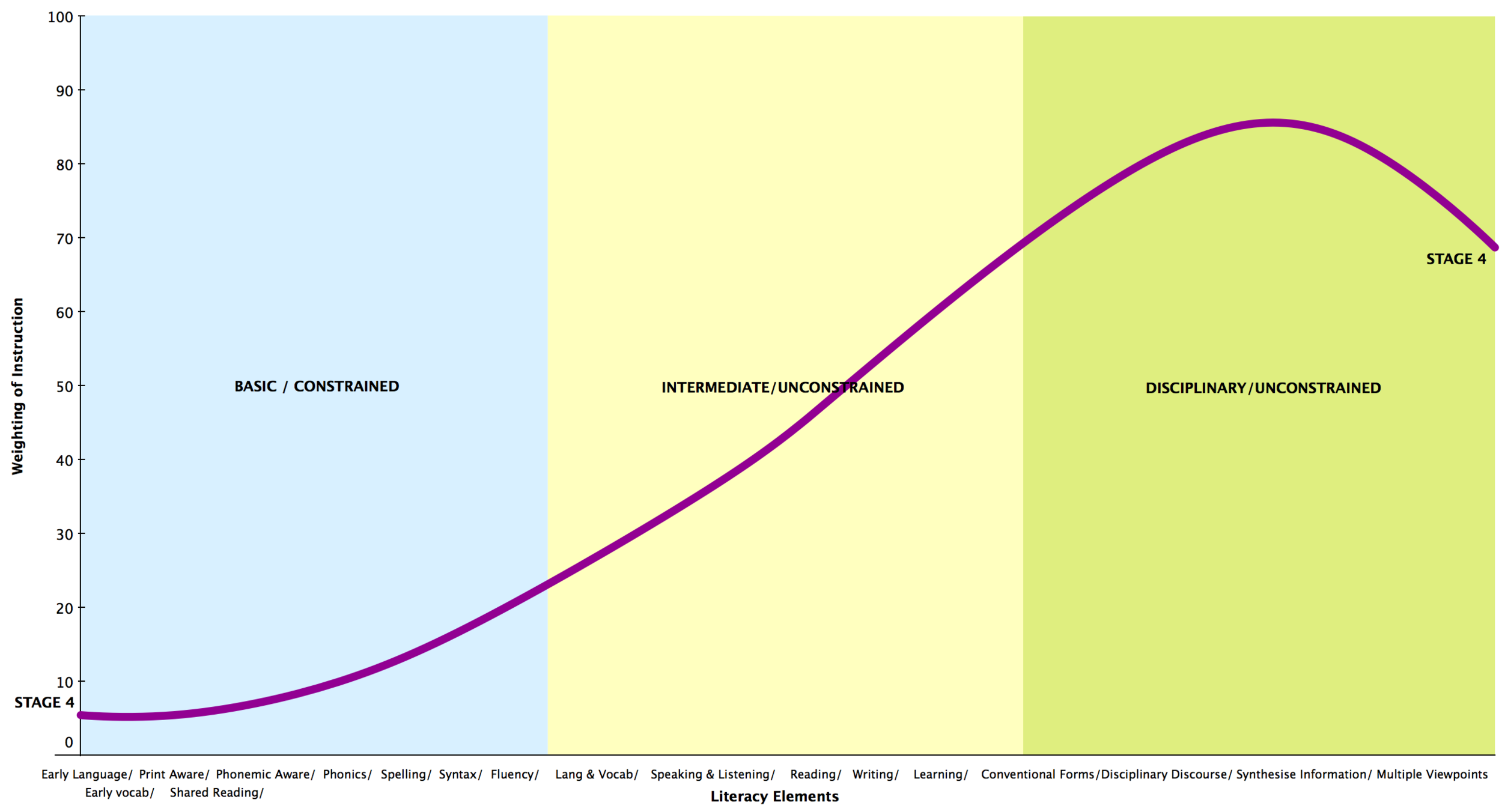

By guiding learners from simple to complex structures, teachers can help learners make logical sense of word reading and writing in English. The Word Sorts (or Word Studies) can easily be organised in such a way that the resulting program is consistent with an evidence-based phonics sequence. Over time, students come to master the patterns of English phonology, orthography, and morphology, so they are equipped with the skills to rapidly and accurately read both known and unfamiliar words.

Rather than prolong the introduction, it is best to allow the video to speak for itself. The following video presentation provides a demonstration of this activity along with some essential points and resources. Grab your popcorn, because it is a bit of a long one. (NB: The video can also be found on YouTube at https://youtu.be/HCvYgHk6ODc.)

Ultimately, we want children to decode with confidence and notice the patterns within printed words. As Mark Seidenberg observes, “for a beginning reader, every word is a unique pattern. Major statistical patterns emerge as the child encounters a larger sample of words, and later, finer-grained dependencies.” (Seidenberg, 2017, 92) “Readers become orthographic experts by absorbing lots of data … The path to orthographic expertise begins with practice practice practice but leads to more more more.” (Seidenberg, 2017, 108).

After you watch the video, we encourage you to download resources that are mentioned in the presentation:

You can also access the Word Sort - Activity Cards, which have been organised into key developmental stages.

For Letter-Name-Alphabetic Stage (to be mastered between 4 to 7 years old):

For Within-Word Pattern Stage (to be mastered between 7 to 9 years old):

For Affix-Suffix Stage (to be mastered between 9 to 11 years old):

For Derivational Stage (to be mastered between from 11 years old and older):

We encourage you to check out the book Words Their Way by Donald Bear and colleagues. It's a highly regarded educational resource with a thorough discussion of activities, developmental expectation and assessment tools.

Bear, S., Invernizzi, M., Templeton, S., & Johnston, F. (2014). Words their way: word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling instruction (5th edition). Essex: Pearson.

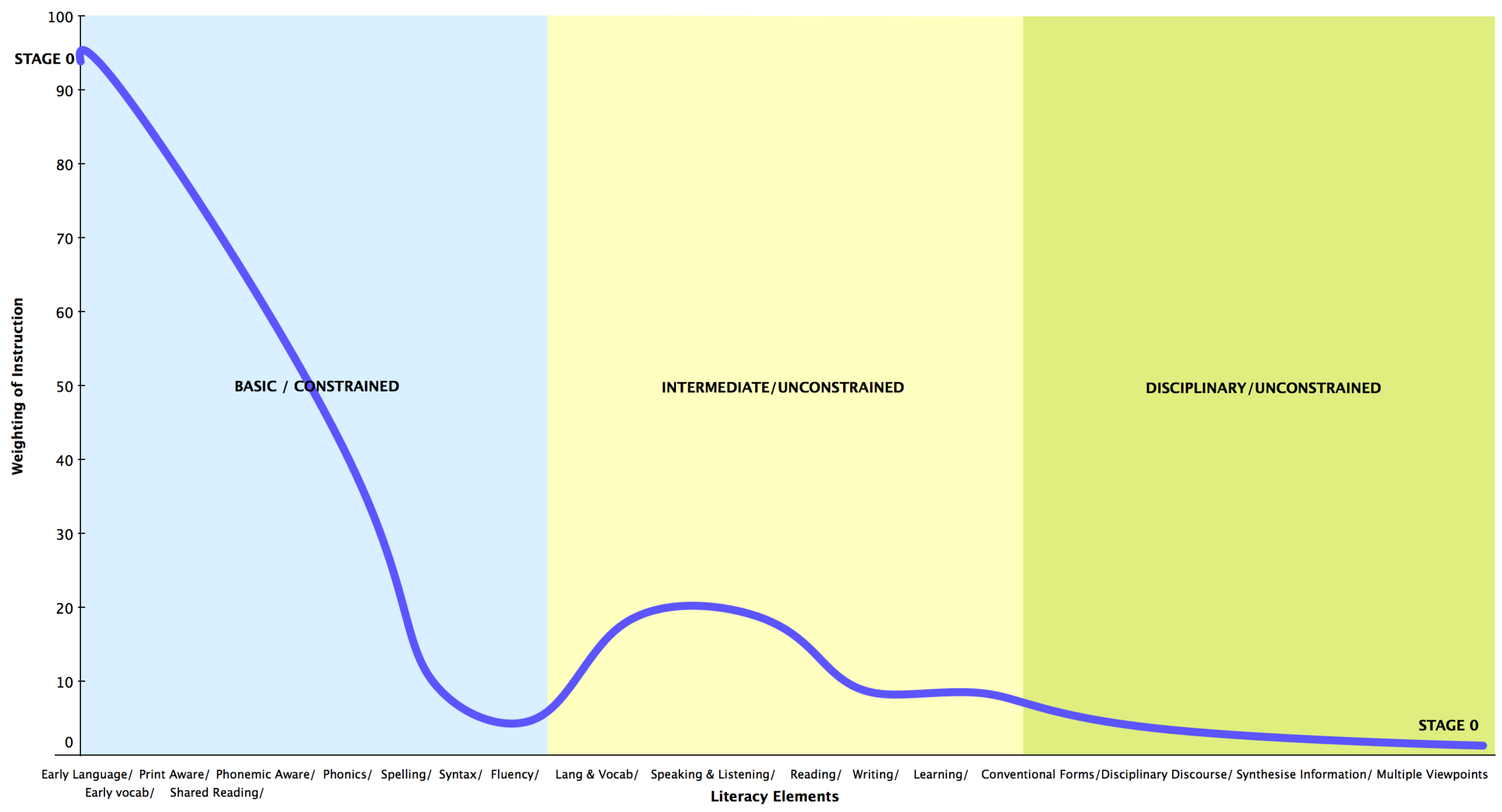

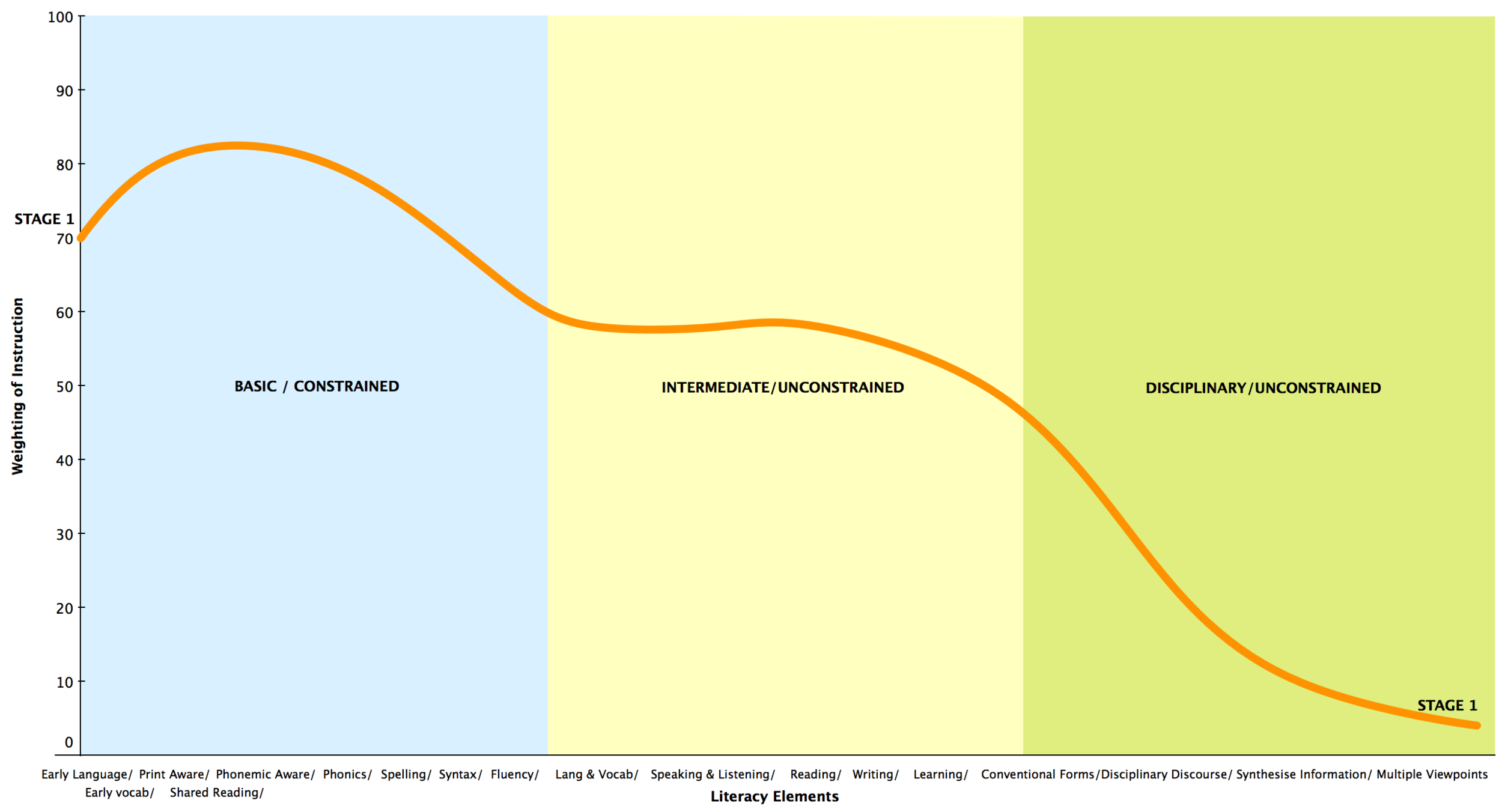

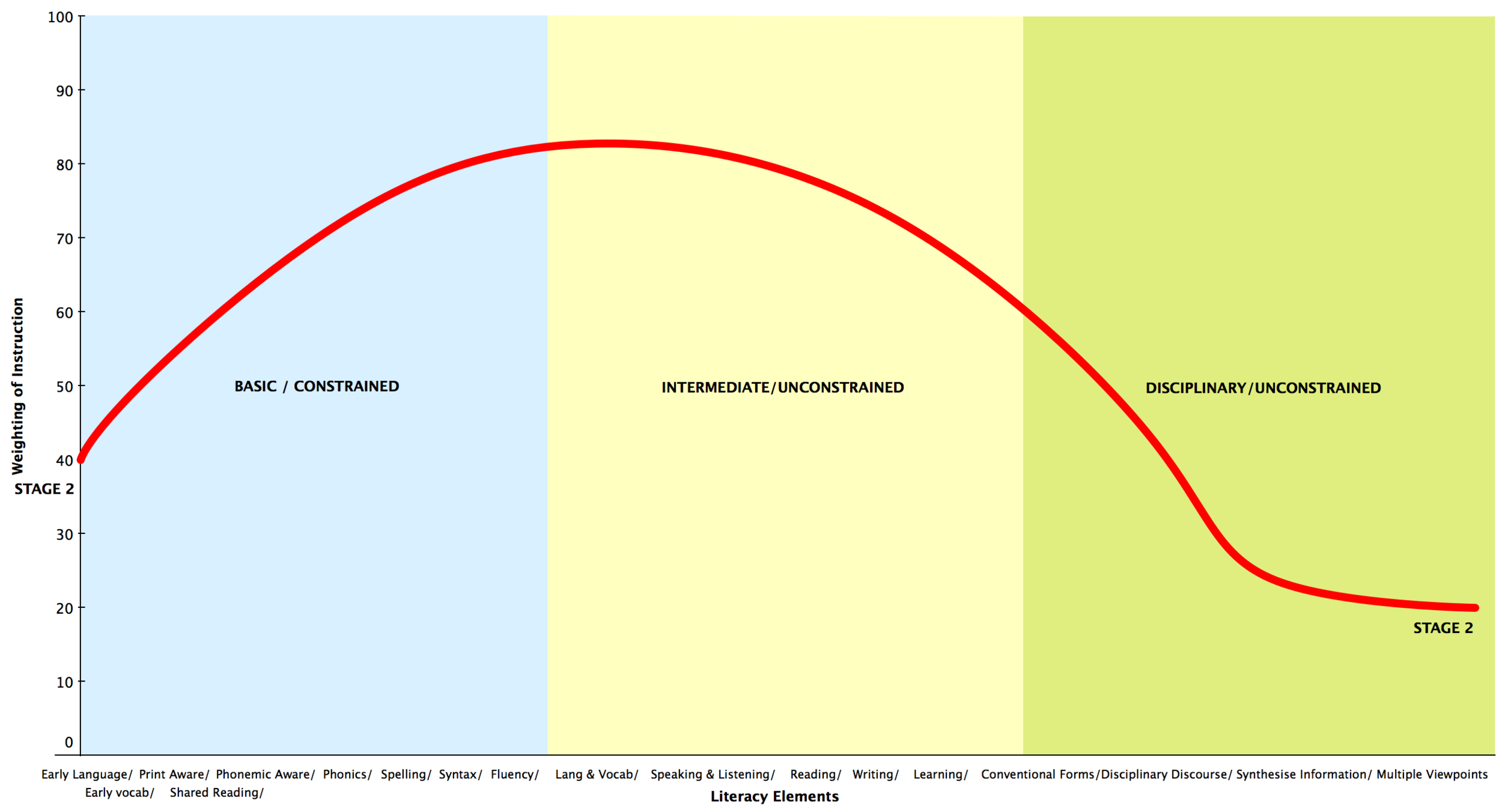

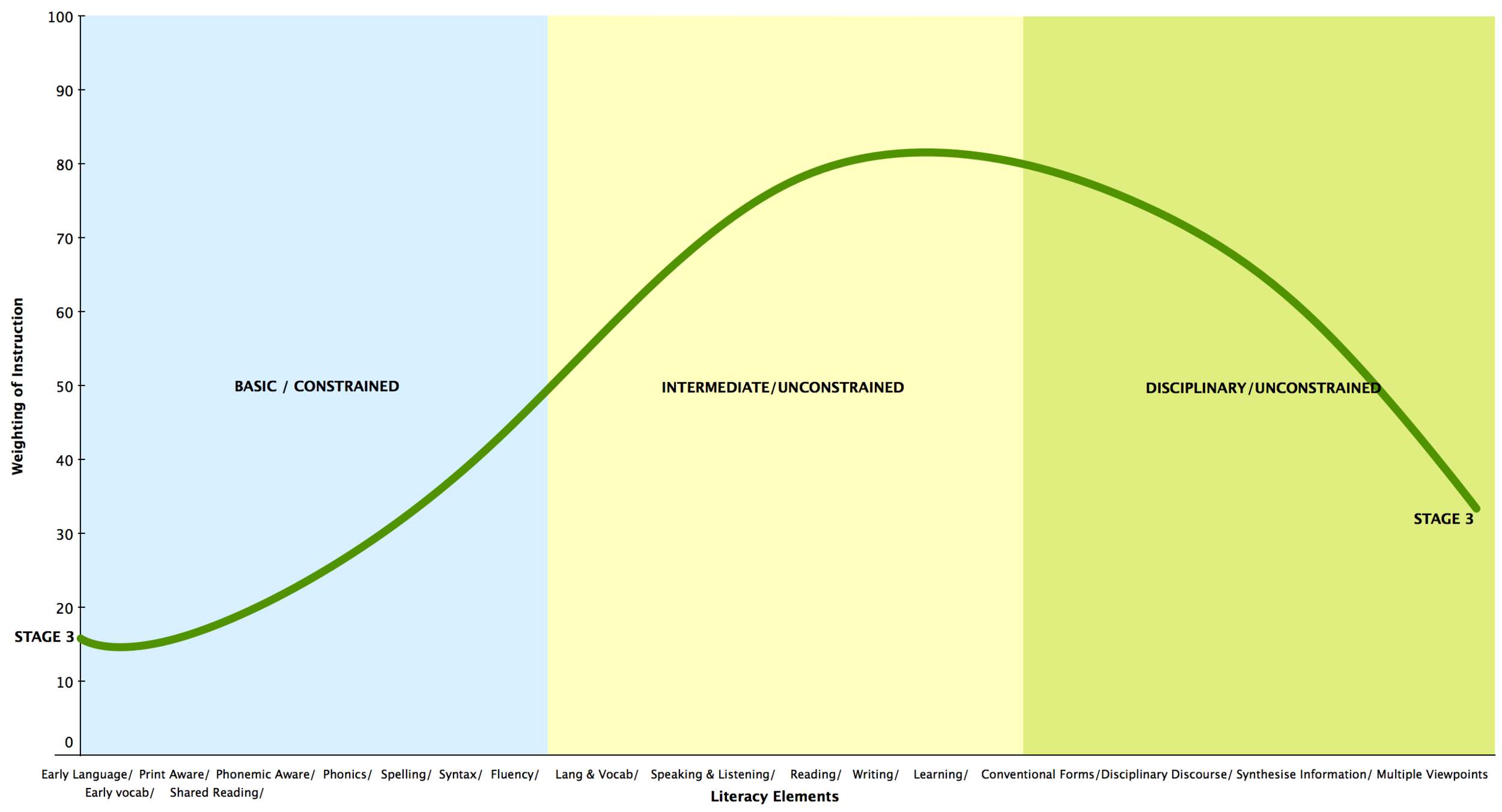

Also, please visit our Mastering the Code presentation, including the presentation slides. This presentation and its associated slides provide background research that will help you better understand the purpose of the activity.

We hope the activity is a valuable addition to your practice. We welcome your feedback and ideas, so please stay in touch.

Thank you for your time. Please explore and enjoy!

References

Bear, S., Invernizzi, M., Templeton, S., & Johnston, F. (2014). Words their way: word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling instruction (5th edition). Essex: Pearson.

Seidenberg, M. (2017). Language at the speed of sight: how we read, why so many can’t, and what can be done about it. New York: Basic Books.