Stages of Literacy Development

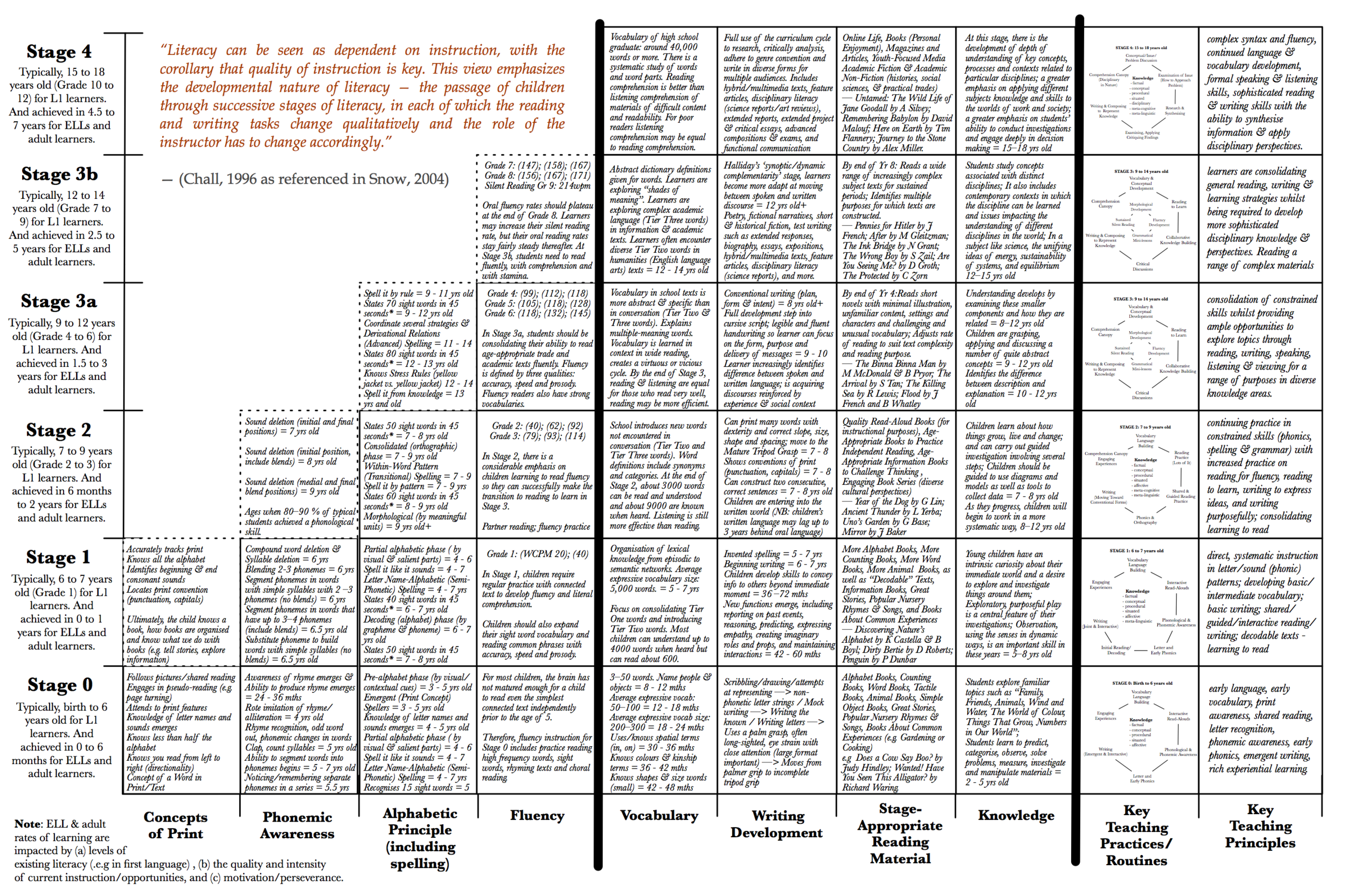

“Literacy can be seen as dependent on instruction, with the corollary that quality of instruction is key. This view emphasizes the developmental nature of literacy — the passage of children through successive stages of literacy, in each of which the reading and writing tasks change qualitatively and the role of the instructor has to change accordingly.”

Considering language and literacy as developmental is really quite fundamental for us. This might sound obvious, which will lead some readers to ask, “what’s all the fuss about? In fact, there isn’t a fuss. Instead, we are noting an emphasis on observing how the capacity of a learner or a group or a class or a community matures over time, but not necessarily so. We place an emphasis on a developmental approach because we are sensitive to the long journey of acquiring the rich skills that will prepare learners “to enter adulthood with the skills they will need to participate fully in a democratic society." (Gambrell, Malloy & Mazzoni, 2011, p. 18) The child (or emerging learner) is not faced with the prospect of developing such complex skills from the get go. There should be a progressive, temporal dimension to this learning where the child is supported by others to develop foundational skills which lead into competencies which lead to mastery which leads to further disciplinary practices.

If we borrow Wittgenstein’s concepts here, we are curious to see how perception (aspect seeing) changes, practices form, attitudes develop, knowledge takes shape, institutions arise and (literate) forms of life take root (or fail to do so). We need to marvel at how learning transpires and how each new act of learning builds from that which came before. We need to marvel at the small steps and giant leaps that occur. We need to be cautious of stagnation and entropy. Ultimately, a developmental perspective is one that recognises the “unfinishedness of the human condition. It is in this consciousness that the very possibility of learning, of being educated, resides ... This permanent movement of searching creates a capacity for learning not only in order to adapt to the world but especially to intervene, to re-create, and to transform it.” (Freire, 1998, p. 66)

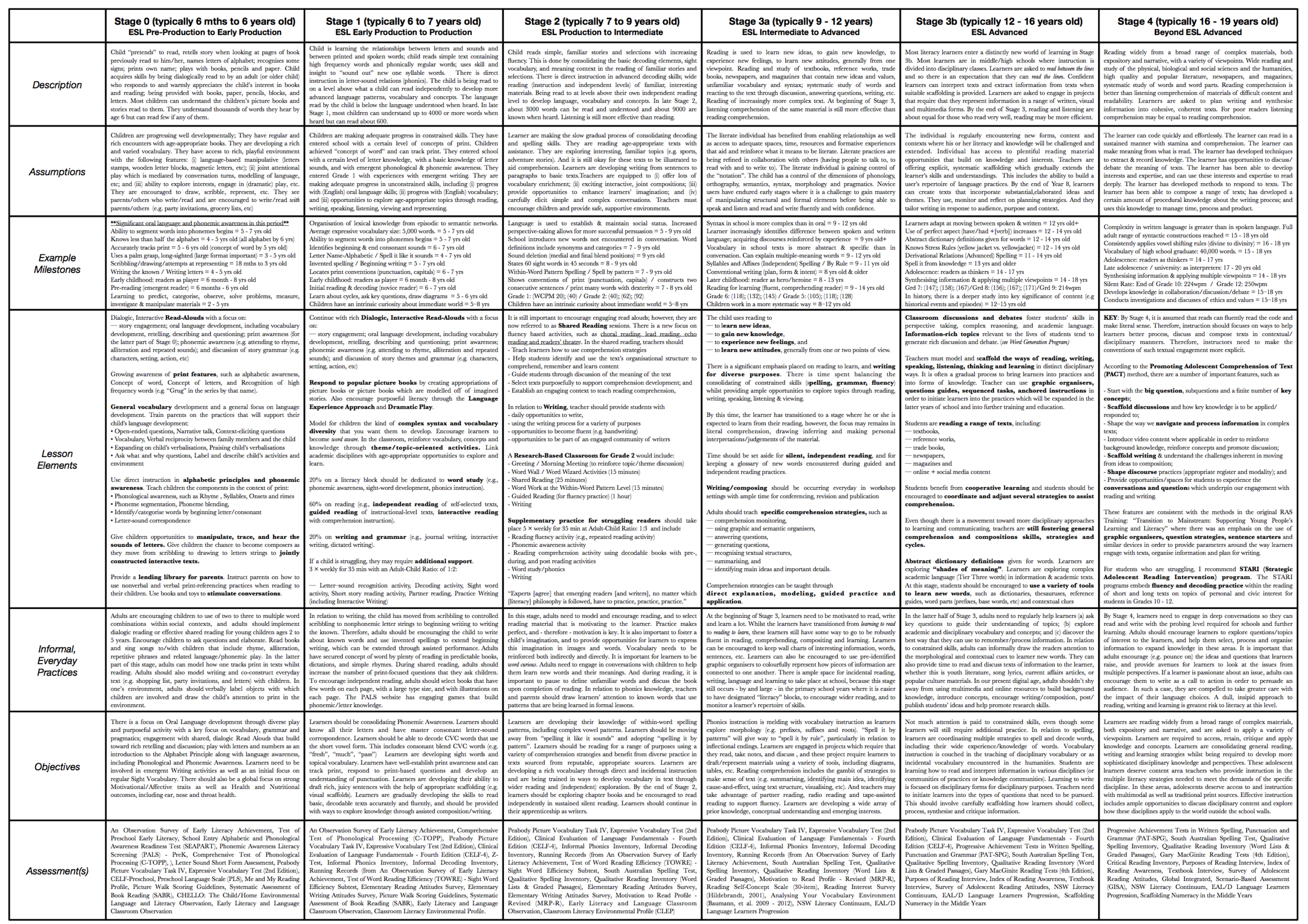

Chall, J. S. (1996). Stages of reading development (2nd ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovic College Publishers. (click here to download chart)

For the purposes of this section of the site, we will use Chall’s (1996) six stages of reading development as a framework, which accounts for reading development from birth to adulthood. These learners lifespan is divided into six stages, which are summarised to in the table to the left. (Once you have the knowledge of the present framework, we invite you to explore further developmental sequences [Footnote 1] as well as the background notes found elsewhere on the site.)

In Stage 0 (pre-reading), typically between the ages of 6 months to 6 years old, the child pretends to read, gradually develops the skills to retells stories when looking at pages of books previously read to him/her. The child gains the ability to name letters of the alphabet, prints own name and plays with books, pencils and paper. By six years old, the child can understand thousands of words but can read few (if any). In this stage, adults are encouraged to scaffold child’s language attempts through parallel talk, expanding on verbalizations and recasting child’s verbalizations. Adults are encouraging children to use of two to three word combinations within social contexts, and adults should implement dialogic reading or effective shared reading for young children ages 2 to 5 years. Any instruction (phonics, vocabulary) should be linked to the book reading, and such books should include rhyme, alliteration, and repetitive phrases. In one’s environment, adults should verbally label objects with which children are involved and encourage children to ask questions and elaborate on observations (Westberg, et al., 2006).

In Stage 1 (initial reading, writing and decoding), typically between the ages of 6 and 7 years old, the child is learning the relation between letters and sounds and between print and spoken words. The child is able to read simple texts containing high frequency words and phonically regular words, and uses skills and insight to “sound out” new words. In relation to writing, the child is moving from scribbling to controlled scribbling to nonphonetic letter strings. Adults are encouraging the child to write about known words and use invented spellings to encourage beginning writing, which can be extended through assisted performance. In this stage, the main aims are to further develop children’s phonological awareness, letter-sound knowledge, and ability to manipulate phonemes and syllables (segmentation and blending). These skills should be taught in the context of print, and children should have ample opportunities to manipulate, trace, and hear the sounds of letters. To encourage independent reading, adults should select books that have few words on each page, with a large type size, and with illustrations on each page. During shared reading, adults should increase the number of print-focused questions that they ask children. Literacy instruction should incorporate listening to stories and informational texts read aloud; learning the alphabet; reading texts (out loud and silently); and writing letters, words, messages and stories. Teachers and parents must ensure that children have ample opportunity to apply practices and strategies. (Westberg, et al., 2006).

In Stage 2 (confirmation and fluency), typically between the ages of 7 and 8 years old, the child can read simple, familiar stories and selections with increasing fluency. This is done by consolidating the basic decoding elements, sight vocabulary and meaning context in the reading of common topics. The learner’s skills are extended through guided read-alouds of more complex texts. By this stage, adults should be providing instruction that includes repeated and monitored oral reading. Teachers and parents must model fluent reading for students by reading aloud to them daily and ask students to read text aloud. It is important to start with texts that are relatively short and contain words the students can successfully decode. This practice should include a variety of texts such as stories, nonfiction and poetry, and it should use a variety of ways to practice oral reading, such as student-adult reading, choral (or unison) reading, tape-assisted reading, partner (or buddy) reading and reader’s theatre. In this stage, vocabulary needs to be taught both indirectly and directly. Adults need to engage in conversations with children to help them learn new words and their meanings. And during reading, it is important to pause to define unfamiliar words and discussing the book upon completion of reading (Westberg, et al., 2006). At the end of this period, the learner is transitioning out of the learning-to-read phase and into the reading-to-learn phase.

In Stage 3 (reading to learn the new), typically developed between the ages of 9 and 13 years old, reading is used to learn new ideas, to gain new knowledge, to experience new feelings, to learn new attitudes, generally from one or two points of view. There is a significant emphasis placed on reading to learn, and writing for diverse purposes. There is time spent balancing the consolidating of constrained skills (spelling, grammar, fluency) whilst providing ample opportunities to explore topics through reading, writing, speaking, listening & viewing. By this time, the learner has transitioned to a stage where he or she is expected to learn from their reading. Adults should teach specific comprehension strategies, such as comprehension monitoring, using graphic and semantic organizers, answering questions, generating questions, recognising textual structures, summarising, and identifying main ideas and important details. Comprehension strategies can be taught through direct explanation, modeling, guided practice and application. Students benefit from cooperative learning and students should be encouraged to coordinate and adjust several strategies to assist comprehension. At this stage, students should be encouraged to use a variety of tools to learn new words, such as dictionaries, thesauruses, reference guides, word parts (prefixes, base words, etc) and contextual clues (Westberg, et al., 2006).

In the penultimate Stage 4 (synthesising information and applying multiple perspective), typically between 14 and 17 years old, learners are reading widely from a broad range of complex materials, both expository and narrative, and are asked to apply a variety of viewpoints. Learners are required to access, retain, critique and apply knowledge and concepts. Learners are consolidating general reading, writing and learning strategies whilst being required to develop more sophisticated disciplinary knowledge and perspectives. These adolescent learners deserve content area teachers who provide instruction in the multiple literacy strategies needed to meet the demands of the specific discipline. In these areas, adolescents deserve access to and instruction with multimodal as well as traditional print sources. Effective instruction includes ample opportunities to discuss disciplinary content and explore how these disciplines apply to the world outside the school walls. Adults should encourage learners to refine interest, pursue areas of expertise, and develops the literacies reflective of the years ahead in post-school contexts (International Reading Association, 2012).

In the final Stage 5 (critical literacy in work and society), reading is used for one’s own needs and purposes (professional and personal). Reading serves to integrate one’s knowledge with that of others to synthesise information and to create new knowledge. Reading and writing is purposeful, strategic, often specialised and anchored. "Literacy" stratifies greatly in adulthood, since our reading and writing habits are shaped by educational, cultural and employment factors that become increasingly diverse in the post-school landscape. In professional and specialised settings, individuals are required to synthesis information from a diverse range of sources in order to form conclusions, shapes audiences views, and navigate multiple points of views (or perspectives).

Through the stages of development, the teacher’s role is to arrange tasks and activities in such a way that students are developing (Verhoeven and Snow, 2001). The teacher - therefore - must be "aware of the learning intentions, [know] when a student is successful in attaining those intentions, [have] sufficient understanding of the students’ prior understanding as he or she comes to the task, and [know] enough about the content to provide meaningful and challenging experiences so that there is ... progressive development” (Hattie, 2012, pp. 19). As noted by Snow (2004), “literacy can be seen as dependent on instruction, with the corollary that quality of instruction is key. This view emphasizes the developmental nature of literacy -- the passage of children through successive stages of literacy, in each of which the reading and writing tasks change qualitatively and the role of the instructor has to change accordingly." (Chall, 1996 as referenced in Snow, 2004)

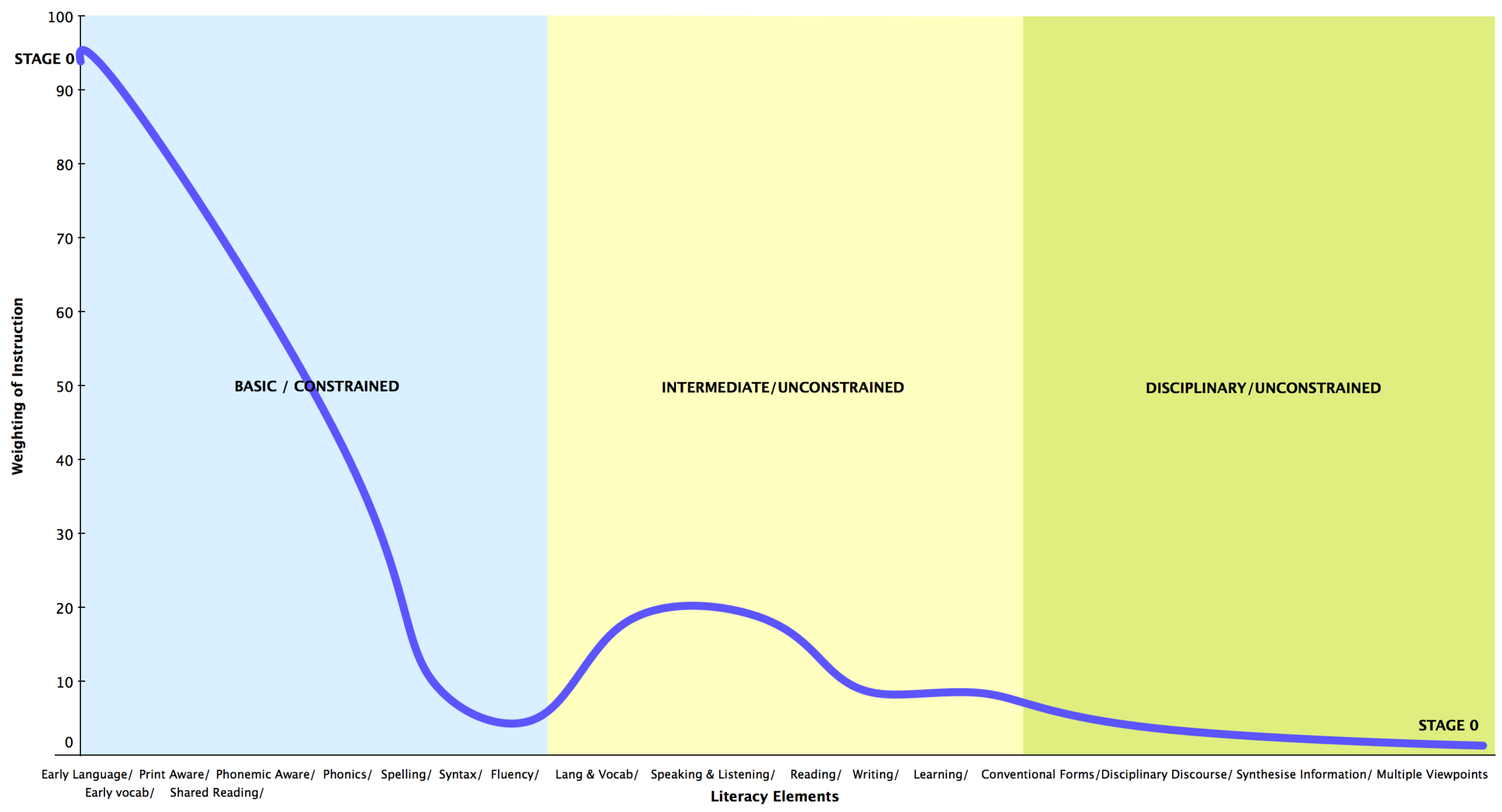

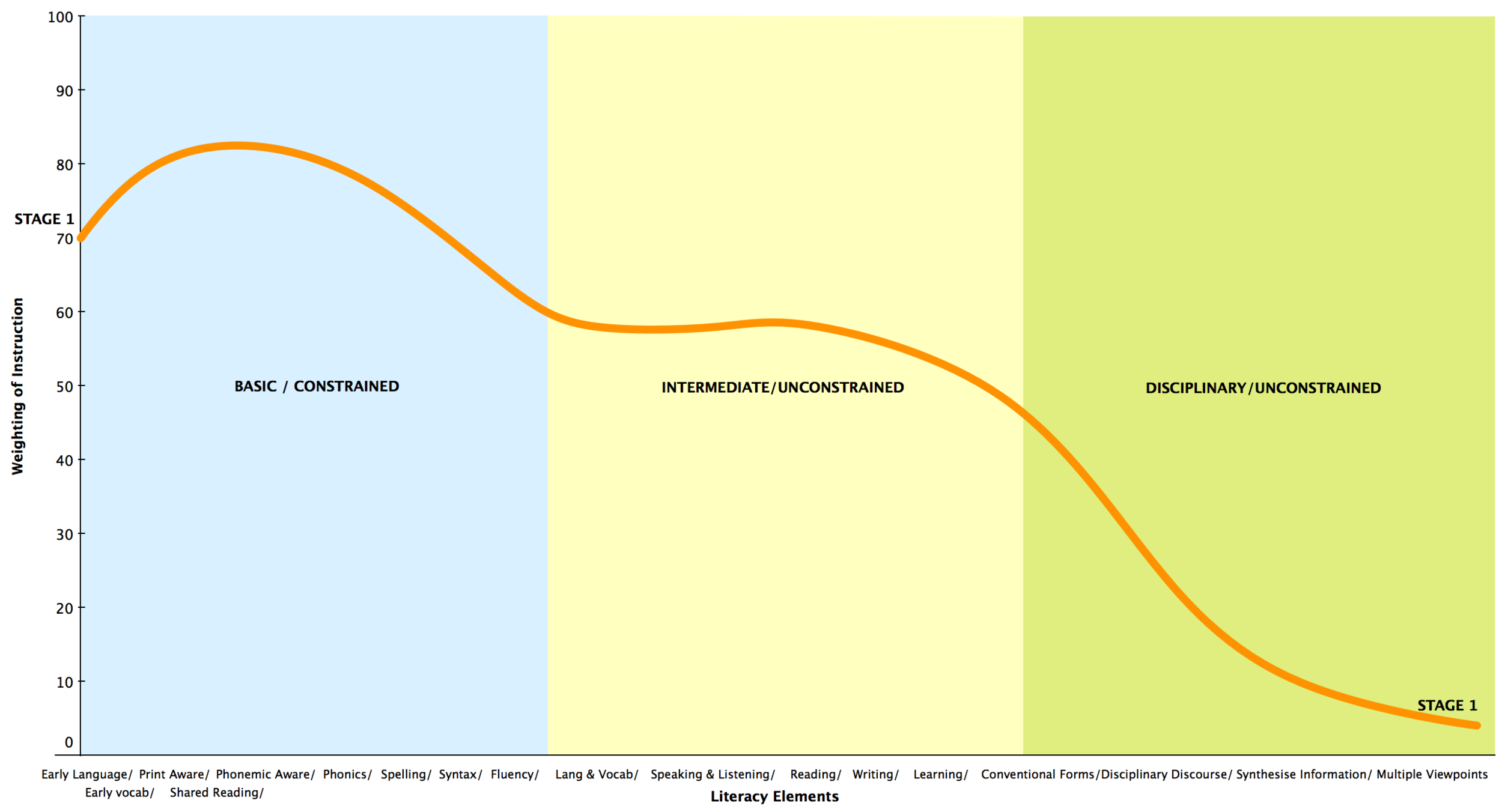

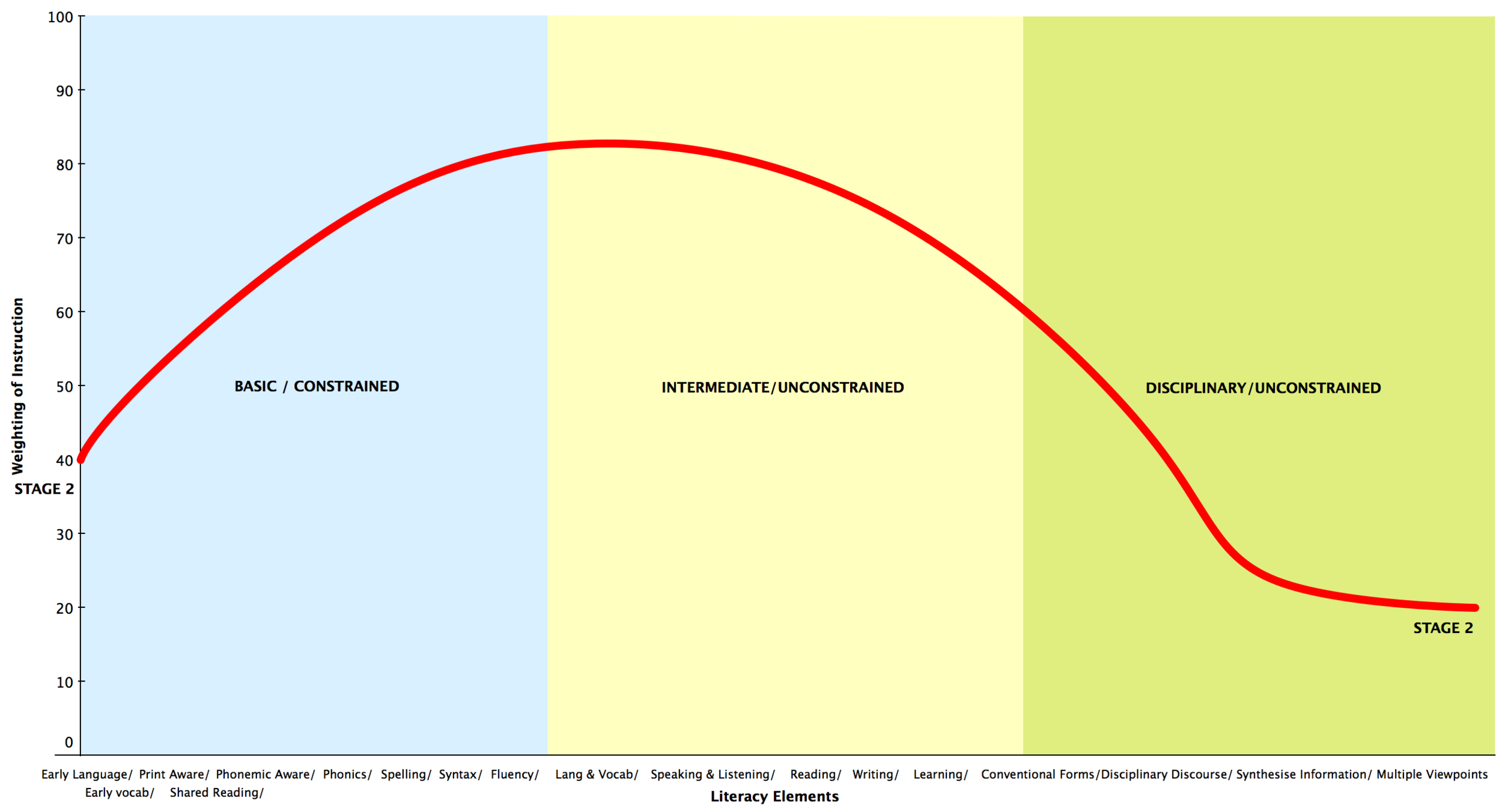

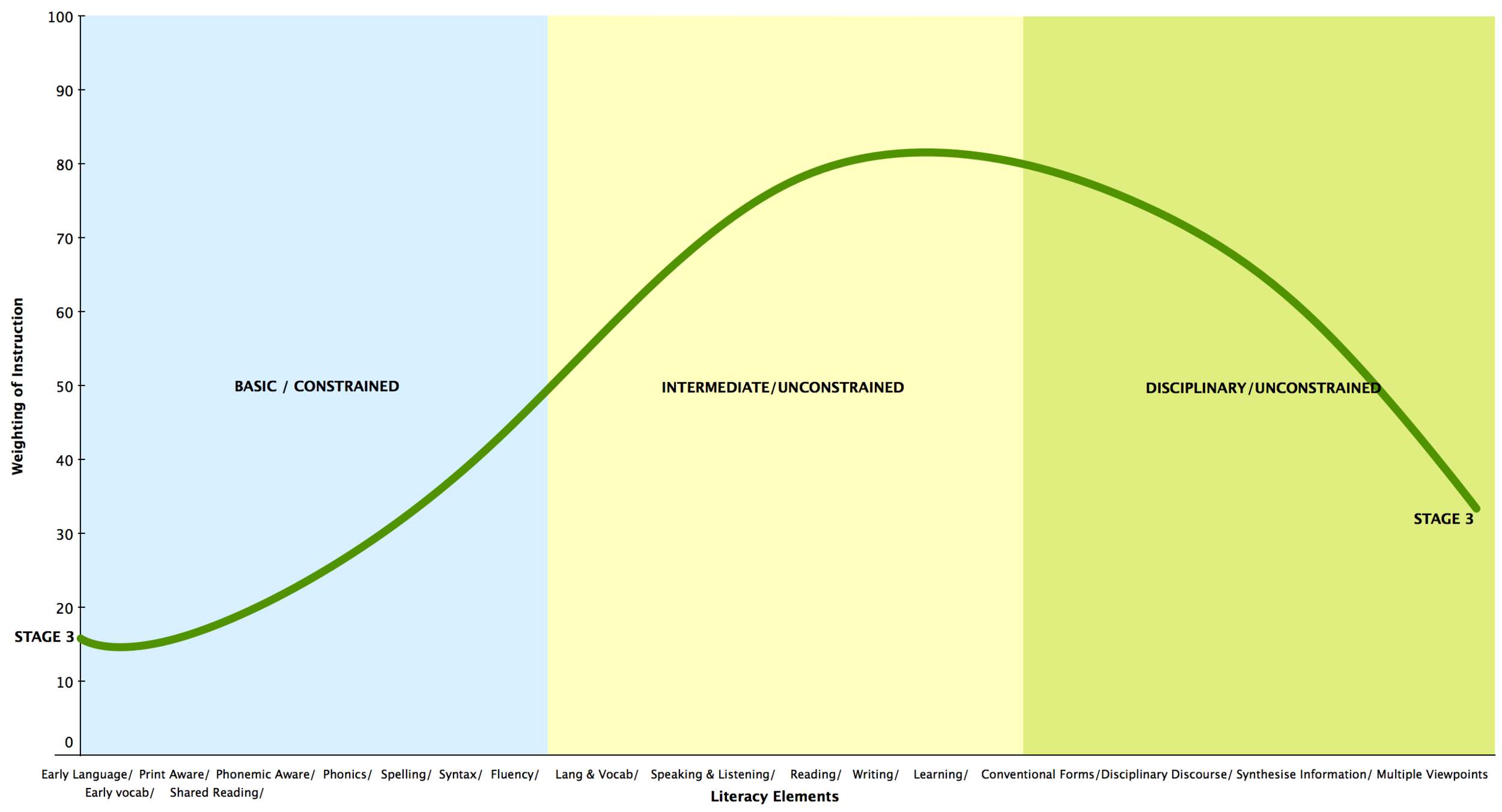

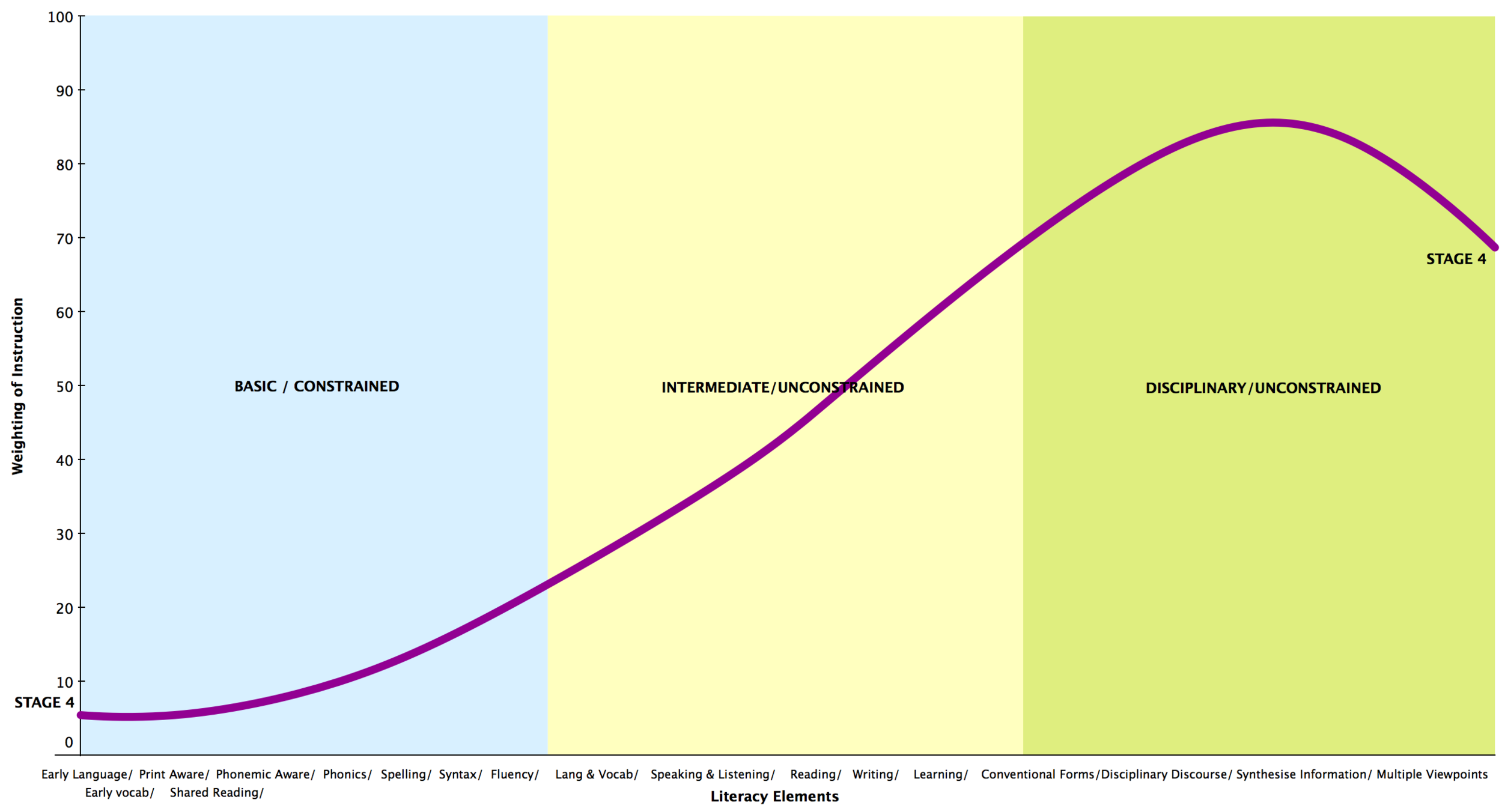

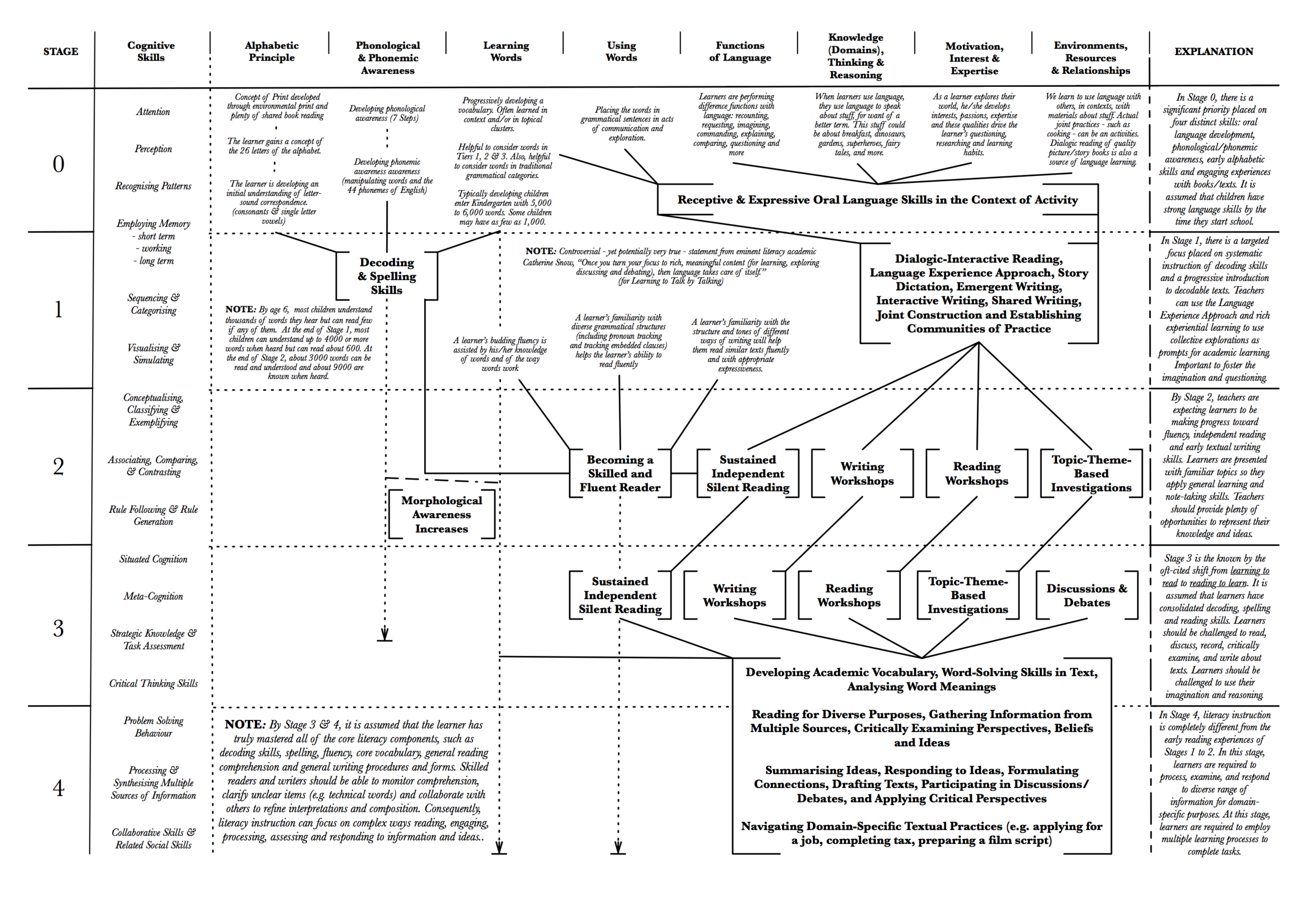

Even though developmental accounts of literacy tend to focus predominantly on the early years, there is the need to account for the "long term developmental process ... to investigate how reading develops across the lifespan by building on the vast literatures in developmental psychology, cognitive psychology, expertise, motivation, and domain-specific learning, as well as reading research" (Anderson, 2007, pg. 415). In her article "The Paths to Competence", Patricia Anderson (2007) notes three domains that develop as a reader develops. These domains are represented in the three graphs that appear below, which bear an uncanny resemblance (schematically, at least) to the graphs (above). We've also added a fourth table from Olson (2007) that indicates cognitive strategies that must be fostered over time as learners develop mature, rich comprehension skills.

The following are the three changes that occur as readers progress from the beginning (or acclimation) phase through to the competence stages and on to the status of proficient or expert readers:

First, the individual's topic/subject-matter knowledge must grow in tandem with one's "domain" knowledge of the attributes of reading. Consequently, early guided reading experiences of picture books require children to demonstrate limited knowledge in either subject or domain knowledge in order to engage in rich, reading on the lap of a caring adult. However, reading (domain) knowledge and topic knowledge become "increasing interconnected as individuals achieve competence" as background knowledge becomes more pivotal to comprehension and as individuals are expected to extract and process information more independently.

Second, in the early stages, individuals are motivated predominantly through "situational interest" such as the people involved (e.g. parents) and their enthusiasm, as well asaccess to engaging books and resources. However, as time passes, individuals are motivated more by individual interests, such as preferred topics, goals and aspirations, and the formation of identities. These interest-driven factors also determine emerging tastes and areas of expertise.

Third (and perhaps most importantly), readers move from a reliance on surface-processing strategies to an increasing use of deep-processing strategies. Surface-processing strategies include such procedures as "[sounding out new words], rereading, altering reading rate, or omitting unfamiliar words" to monitor comprehension/attention. These strategies help one stay on task, correct mistakes, and gain a literal understanding of texts. Deep-processing strategies include "cross-text comparisons, creating alternative representations or questioning a source." Deep-processing strategies focus greater energies on synthesing, analysing and "gain the gist of" texts. They rely upon fluency to be developed so that more sophisticated higher order strategies can be applied.

Therefore, teaching strategies must develop core skills whilst also challenging readers. Classrooms and whole schools should promote "a coherent curriculum [that] helps students ... acquire basic skills as well as the strategies needed to tackle challenging tasks (Newmann, Smith, Allensworth & Bryk, 2001). We are aiming to reach a state whereby, "success builds on success, because as students gain confidence, they are willing to work harder and can more readily learn.” (Au, 2005, pp 175). To work toward this aim "what ... [is] needed is ... a theory of social learning which would indicate what in the environment is available for learning, the conditions of learning, the constraints on subsequent learning, and the major reinforcing processes.” (Bernstein, 1964, pg. 55)

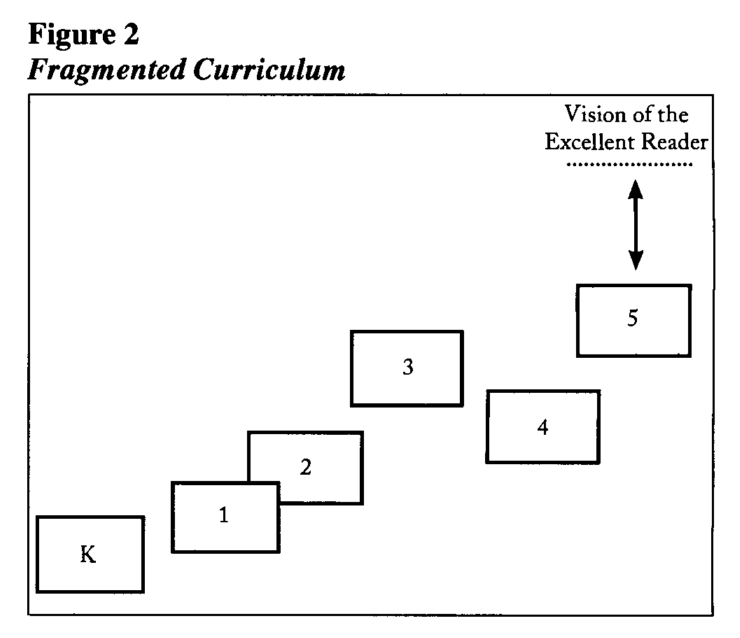

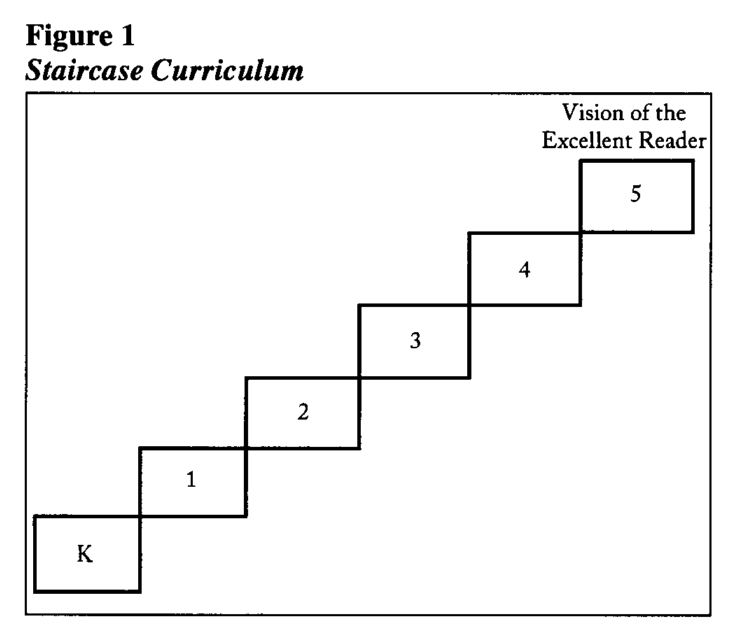

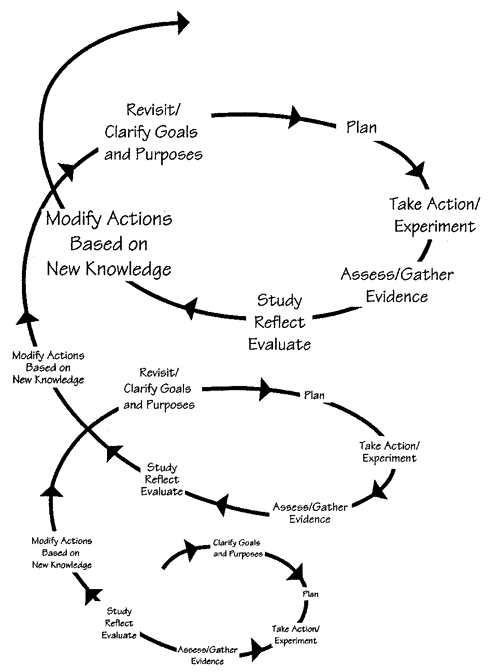

As an illustration, the images to the left attempt to represent the contrast between a fragmented approach to teaching and a more coordinated one. Figure 2 (Au & Raphael, 2011) represents an all-too-common picture in schools, classrooms and homes. In such cases, there are lots of literacy, language and learning activities occurring but in a fragmented and less coordinated manner. Figure 3 (Au & Raphael, 2011), illustrates a progressive development of skills, however, it is one which lacks balance. For example, the image represents a school that provides robust, challenging and direct instruction of decoding and language development in the early years; however, the rigour of instruction and the scaffolding in vocabulary, comprehension and composition begin to wane after Year 3. This phenomenon is not uncommon and is known as the “fourth grade slump” (Chall, Jacobs & Baldwin, 1990). The ideal images are depicted in the third and fourth images, where there is robust instruction at each stage in Figure 1 (Au & Raphael, 2011), and where each stage is seen as extending the skills of the previous activities in the fourth “spiral curriculum” image (Costa & Kallick, 1995),

Therefore, we must ask ourselves: what capacities are being developed at each level of development? What are learners doing now that they couldn’t do before? How can today’s learning build on yesterday’s to prepare for tomorrow’s? How are changes occurring in this person/group/class/community? What future changes and demands can we foresee? What individual changes need to take place for sustainable practices to be in place? What structural changes are required? And what are the cultural implications?

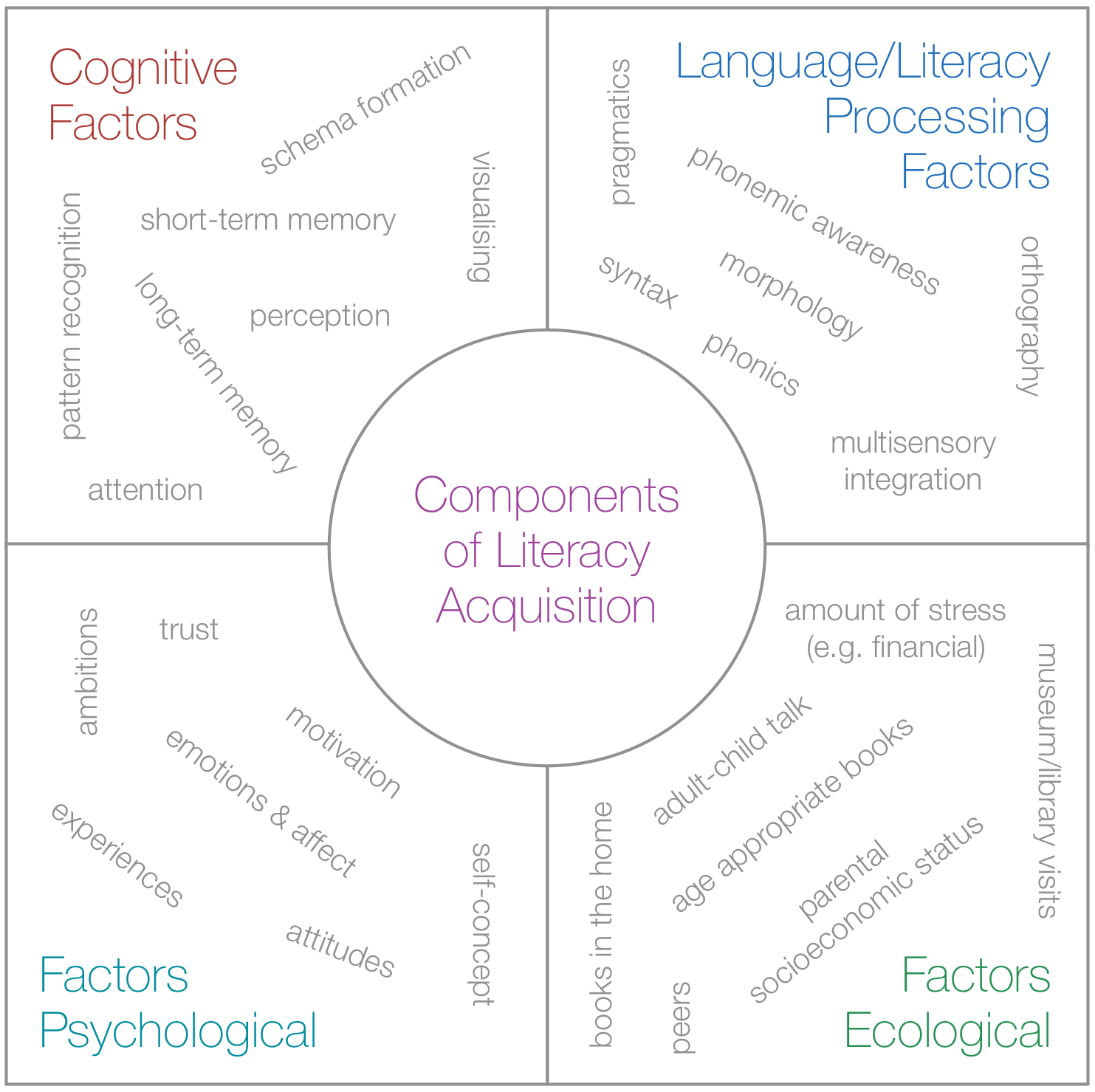

If you permit us to digress, we must ask ourselves, “what would be in contrast to a developmental perspective? Why wouldn’t one hold a developmental approach?” Well, if we fail to see things from the learner’s eyes, if we fail to alter or extend our teaching as learners progress, and/or if we fail to appreciate a learner’s prior knowledge and current interests, then we would fail to adopt a developmental perspective. Also if we failed to take into considerations the ecological, psychological and cognitive factors that impact a learner, then we would also fail to adopt a developmental approach (Chiu, McBride-Chang & Lin, 2012). If we are lured into one-size-fits-all solutions or pedagogies that remains static despite changing conditions, then we fail to consider the developmental conditions of individual learners and classes and school populations. A developmental perspective impacts the books we choose, the topics we pursue, the support strategies that are in place, and the objectives of our teaching and learning.

In the end, we must be realistic about the consequences of inaction. In other words, we must understand why it is essential to establish routines and formative assessment so that gradual practice, planning and development can occur before potential issues become problems. Despite popular opinion, literacy does not develop naturally, with ease and without the need for direct instruction and regular practice. We should be enthusiastic about new practices, aware of the significance of daily growth and mindful about the importance of special moments.

We must acknowledge that the instruction for students who at risk of reading delays needs to be “more explicit and comprehensive, more intensive, and more supportive than the instruction required by the majority of children.” (Foorman & Torgesen, 2001) It is through this frame that we acknowledge that suitable instruction for one child/learner may not be suitable for another. That is, embedded phonemic awareness in rich guided reading may be clearly effective for early learners with moderate to high literacy skills entering school, however, low literate learners require additional intensive and systematic focus on decoding skills to make comparable gains. (Foorman & Torgesen, 2001; Chall, Jacobs & Baldwin, 1990). Consequently, teachers need to have access to suitable materials, effective professional development and the ability to modify instruction based on learners’ needs (Foorman & Torgesen, 2001).

"Word reading is the best predictor of reading comprehension level in the early years (Juel, Griffith & Gough, 1986); but others skills (e.g. background knowledge, inferring, summarising, etc) become more important predictors of comprehension level as word reading ability develops through experience (Curtis, 1980; Saarnio, et al., 1990). Thus, the relative importance of different skills may change during the course of development." (Cain, Oakhill & Bryant, 2004, p. 32)

Research has found that structure and challenge are key components of effective literacy and language instruction (Chall, Jacobs & Baldwin, 1990). Learners should have the opportunity to consolidate current skills and knowledge (that they are expected to complete independently at the current stage) whilst experiencing more advanced skills and knowledge (that they can complete through the assistance/scaffolding/modelling of experienced adults). Too often literacy instruction will stagnate at one level without providing the instructional momentum, opportunities, and experiences necessary for further stages of development. The above is easier said than done, and Chall, Jacobs and Baldwin (1990) acknowledge that the strongest characteristics of instrucion are the qualities of the teacher - which can be the dual efforts of parents and teachers - and the structure (and time allotted) in the classroom and in the home. When the structure lacks balance, then it is difficult to consolidate skills and to integrate new, extended elements of language, literacy and learning.

Chall's colleague Catherine Snow equally acknowledges the importance of effective home practices and emotional support if children are to continue on the pathways to being resilient, motivated and successful learners (Snow et al, 1991), whilst it is essential that learning pathways respect/acknowledge the daily, child-rearing practices of diverse cultures (Hemphill & Snow, 1996; Au & Mason, 1981). And in the busy life of teachers, children, youth and adults, it is essential that physical and temporal spaces are carved out for real, effective, consolidated development of literacy (Bartlett & Holland, 2002). When conditions (including policy) allow for such spaces to be allocated for cohesive learning, then deep discourses can be fostered with sufficient time to develop skills and expertise (Gebhard, 2005). When conditions work against one, it may feel like one is trying to swim upstream (Gebhard, 2002).

In time, we will address the following sequence of questions for each of Chall's six stages of reading development.

1. What does instruction look like at this stage?

activities, routines, etc;

books and other texts;

writing tasks; and

formal and informal activities;

3. What would gradual release of control (or apprenticeship) look like at this stage?

2. What should learners be able to accomplish/engage in?

independently;

with guidance;

jointly;

if/when modelled.

4. At the end of the stage, how is the learner prepared for the subsequent stage?

5. What would be characteristic age range be for this stage? What support/intervention should be provided if a learner is failing behind?

6. How does one coordinate learning/support if there is a substantial difference between the learner's age and developmental stage? How does one choose content that is both linguistically and age appropriate?

7 How can we use the component model of literacy development (depicted above) to (a) identify potential assets/deficits exhibited by the learners and (b) to strategise with a multi-dimensional approach to building capacity in each area?

Footnote 1: (back to top)

The following are texts that provide guidance on developmental sequences of language/literacy.

Adlof, S. M., Perfetti, C. A., and Catts, H. W. (2011). Developmental changes in reading comprehension: implications for assessment and instruction. In What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed., pp. 186 – 214). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2014). English as an Additional Language or Dialect Teacher Resource EAL/D Learning Progression: Foundation to Year 10. Sydney.

Chall, J. S. (1996). Stages of reading development (2nd ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovic College Publishers.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The Reading Crisis: Why Poor Children Fall Behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Curriculum Corporation. (1997). ESL Scales. Melbourne: Curriculum Press.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2007). The Continuum of Literacy Learning (K-8): Behaviours and Understandings to Notice, Teach and Support. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Lust, B. (2006). Child language: acquisition and growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKenna, M. C., & Stahl, K. A. D. (2009). Assessment for reading instruction (ebook) (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2010). The Literacy Learning Progressions: Meeting the Reading and Writing Demands of the Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media Limited.

NSW Department of Education and Communities. (2011). NSW Literacy Continuum. NSW Department of Education and Training. Retrieved July 26, 2014, from http://www.curriculumsupport.education.nsw.gov.au/literacy/

Paris, S. G. (2005). Reinterpreting the development of reading skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(2), 184–202. doi:10.1598/RRQ.40.2.3

Stahl, K. A. D. (2011). Applying new visions of reading development in today’s classroom. The Reading Teacher, 65(1), 52–56. Retrieved from http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/scmsAdmin/uploads/006/717/new visions.pdf

Wolf, M. (2008). Proust and the squid: the story and science of the reading brain. Cambridge: Icon Books.

References: (back to top)

Alexander, P. A. (2005). The Path to Competence: A Lifespan Developmental Perspective on Reading. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(4), 413-436.

Au, K. H.-P. (2005). Negotiating the Slippery Slope : School Change and Literacy Achievement. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(3), 267–286.

Au, K. H.-P., & Mason, J. M. (1981). Social Organizational Factors in Learning to Read: The Balance of Rights Hypothesis. Reading Research Quarterly, 17(1), 115. doi:10.2307/747251

Au, K. H.-P., & Raphael, T. E. (2011). The staircase curriculum: whole-school collaboration to improve literacy achievement. New England Reading Association Journal, 46(2), 1–8.

Bartlett, L., & Holland, D. (2002). Theorizing the Space of Literacy Practices. Ways of Knowing, 2(1), 10 – 22.

Bernstein, B. (1964). Elaborated and Restricted Codes: Their Social Origins and Some Consequences. American Anthropologist, 66(6_PART2), 55–69. doi:10.1525/aa.1964.66.suppl_3.02a00030

Cain, K. E., Bryant, P. E., & Oakhill, J. (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: Concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31

Chall, J. S. (1996). Stages of reading development (2nd ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovic College Publishers.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The Reading Crisis: Why Poor Children Fall Behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chiu, M. M., McBride-Chang, C., & Lin, D. (2012). Ecological, psychological, and cognitive components of reading difficulties: testing the component model of reading in fourth graders across 38 countries. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 391–405. doi:10.1177/0022219411431241

Costa, A. & Kallick, B. (1995). Process Design: Feedback Spirals As Components of Continued Learning. In A. Costa & B. Kallick (Eds.) Assessment in the Learning Organization. Alexandra, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Curtis, M. E. (1980). Development of components of reading skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 656–669

Foorman, B. R., & Torgesen, J. (2001). Critical elements of classroom and small-group instruction promote reading success in all children. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 16(4), 203–212.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: ethics, democracy and civic courage. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Gambrell, L., Malloy, J., and Mazzoni, S. (2011). Evidence-based best practices in comprehensive literacy instruction. In L. Morrow and L. Gambrell (Eds.) Best practices in literacy instruction (4th Edition). (pp. 11 - 36). New York: The Guilford Press.

Gebhard, M. (2002). Fast Capitalism, School Reform and Second Language Literacy Practices. Canadian Modern Language Review, 59(1), 15 – 52.

Gebhard, M. (2005). School Reform, Hybrid Discourses, and Second Language Literacies. TESOL Quarterly, 39(2), 187 – 210. doi:10.2307/3588308

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: maximising impact on learning. New York: Routledge.

Hemphill, L., & Snow, C. (1996). Language and literacy development: Discontinuities and differences. In D. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The handbook of education and human development: new models of teaching, learning and schooling (pp. 173–201). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

International Reading Association. (2012). Adolescent Literacy: a position statement of the International Reading Association. Newark, DE.

Juel, C., Griffith, P. L., & Gough, P. B. (1986). Acquisition of literacy: A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78, 243–255

Newmann, F. M., Smith, B., Allensworth, E., & Bryk, A. S. (2001). Instructional Program Coherence: What It Is and Why It Should Guide School Improvement Policy. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(4), 297–321. doi:10.3102/01623737023004297

Olson, C. B., & Land, R. (2007). A cognitive strategies approach to reading and writing instruction for English language learners in secondary school. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(3), 269–303. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000244438000003

Saarnio, D. A., Oka, E. R.,& Paris, S. G. (1990). Developmental predictors of children’s reading comprehension. In T. H. Carr & B. A. Levy (Eds.), Reading and its development: Component skills approaches (pp. 57–79). New York: Academic Press.

Snow, C. (2004). What counts as literacy in early childhood? In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Handbook of early child development. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Snow, C. E., Barnes, W. S., Chandler, J., Goodman, I. F., & Hemphill, L. (1991). Unfulfilled expectations: home and school influences on literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Verhoeven, L., & Snow, C. (2001). Literacy and motivation: bridging cognitive and sociocultural viewpoints. In L. Verhoeven & C. Snow (Eds.), Literacy and motivation: reading engagement in individuals and groups (pp. 1 – 22). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Westberg, L., McShane, S., & Smith, L. (2006). Verizon Life Span Literacy Matrix: Relevant Outcomes , Measures and Research-based Practices and Strategies. Washington D.C.