Early language learners benefit from rich tasks that provide learners with ample opportunities to hear, see, use and manipulate language in contextualised, purposeful ways. The videos to the lower right provide compelling examples of the multiple learnings achieved through a humble kitchen garden project for newly arrived refugee children at a primary school in an urban Australian community. The project illustrates the potential for deep learning when the learning develops from authentic, engaging experiences.

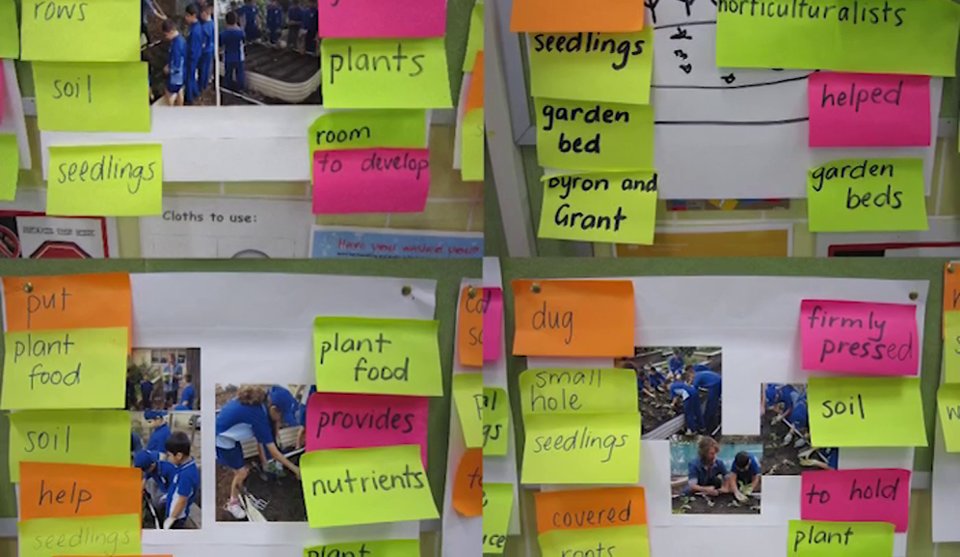

I'd like readers/viewers to notice how the kitchen garden becomes a central device to develop language, literacy, culture and knowledge. You should notice how language is reinforced through practical activity, how language is assisted visually in the classroom, and how it is transformed into knowledge through writing.

This is an example of a teaching method known as the Language Experience Approach (LEA), which is a catch-all term for teaching that anchors literacy and language learning in shared experiences. In most cases, the “experience” is a physically, shared experience, but there is a more and more avenues to share experience virtually through video, interactive tools and online content (such as web quests).

The Language Experience Approach emphasises language learning through carefully scaffolded and reinforced language in context and through activity. Teachers and learners diligently document the experience, so the experience can be revisited and developed through further reading, writing, speaking, listening, viewing and representing in the classroom.

The following are a number of questions to consider when building language and literacy through authentic, mutual practices. Even though we will elaborated on the teaching method in the future, these initial questions illustrate the significance of a number of essential practices in the LEA, such as scaffolded talk, documenting the experience, revisiting the experience in the classroom, pulling out rich vocabulary, expanding the experience through writing, and using the experience for further comprehension and [content] learning. In this system, the teacher must be adept at orchestrating, sequencing and extending a variety practices (often within a tight timetable).

Before and During the Experience

- What is the experience? Is this an actual or virtual experience?

- How is joint attention achieved and how is language being scaffolded?

- How is vocabulary emphasised/reinforced/introduced/recorded during the experience

- How is the experience being documented (digital cameras, information scaffolds, graphic organisers, scaffolded questions, etc)?

- How do the instructional conversations that take place throughout the experience build a common discourse and assist learning?

After the Experience

Students benefit from a variety of activities that reinforce language and literacy in the classroom: word walls, flow charts, exemplary texts and further hands-on learning.

- Are word walls / glossaries / semantic maps / flow charts / storyboards developed from the experience? Are they prominent, accessible and rigorous?

- How is the documentation used to help the class jointly and/or individually re-construct the experience? Is the sentence cycle used to generate rich, juicy sentences?

- How is the joint construction phase used to refresh people’s memory and knowledge of events?

- Can the newly constructed text(s) be used as “familiar text(s)” that can be re-read as fluency practice?

- Has the teacher selected a portion of words to use for further word study?

Extending the Experience

- Can you link new readings to the shared experience? For instance, now that we have explored the world of the garden, can we explore:

- poetry about gardens or which use gardens as a motif;

- procedural/information texts about gardening;

- stories and/or picture books which takes place in a garden; and

- news articles about community gardens?

- Can the writing be extended to the inclusion of the writing of recognised genres related to the experience? (procedural texts, brochures, etc)

- How have non-verbal knowledge, expertise and attitudes been fostered through the activity?

Final Note

The Language Experience Approach (LEA) does not replace systematic, intensive instruction in word study, nor does the LEA replace the importance of regular shared and guided reading of age- and skill-appropriate texts. That said, shared and guided can be incorporated into the LEA. The LEA provides an important avenue for the exploration of guided and extended writing and language learning. Within the LEA, there are many micro-teaching moments which should take advantage of best practice language and literacy methods.

Further Reading

Au, K. H. (1979). Using the Experience-Text Relationship Method with Minority Children. The Reading Teacher, (March), 677–679.

Labbo, L. D., Eakle, A. J., & Montero, M. K. (2002). Digital Language Experience Approach: Using Digital Photographs and Software as a Language Experience Approach Innovation. Reading Online, 5(8), 1–19. Retrieved from http://www.readingonline.org/electronic/labbo2/

Landis, D., Umolo, J., & Mancha, S. (2010). The power of language experience for cross-cultural reading and writing. The Reading Teacher, 63(7), 580–589.

Moustafa, M. (2008). Exceeding the standards: a strategic approach to linking state standards to best practices in reading and writing instruction. New York: Scholastic.

Nessel, D. D., & Dixon, C. N. (2008). Using the language experience approach with English language learners: Strategies for engaging students and developing literacy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Wurr, A. J. (2002). Language Experience Approach Revisited: The Use of Personal Narratives in Adult L2 Literacy Instruction. The Reading Matrix, 2(1), 1–8. Retrieved from http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/wurr/?collection=col10460/1.